Mob Rule

The piñata and the unicorn have something in common for our family. It is an unusual union. Back in the day, I took a swing or two at a piñata, most likely after a couple of beers and the encouragement of the crowd; certainly with no malice to destroy a papier-mâché object or with a craving to have the candied guts shower over my head. It has been a long time since that incident. But this year, I did attend a birthday where a mob was gathered around a piñata and each participant got to take their club-wielding turn at the creature with its belly full of treats.

In June, Kay and I went to Scotland for a couple of weeks. Before our departure, a grand daughter requested we bring her back a unicorn, her current stuffed-animal obsession. I was not aware that Scotland’s national animal was the unicorn. Images of it abound in the country. The unicorn is to Scotland what the bald eagle is to America. And while both creatures have achieved notable status in each nation, we know which one is real. That does not however, take away from the power each one represents.

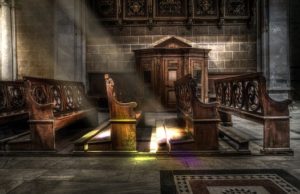

When Kay and I toured Stirling Castle, tapestries of “The Hunt of the Unicorn” were on prominent display. These works of art portray an odd co-mingling of pagan and Christian mythologies. The unicorn has a long history in Scotland dating as far back as William I in the 12th century who used the image in his coat of arms, and King James III who stamped a depiction onto gold coins. While representations fashioned in stain glass, on banners and flags, painted onto coffee mugs and sewn into bath towels were available at every gift shop and street vendor, we purchased a stuffed version of the horned animal in a thrift store of all places, complete with a rainbow-colored mane and tail. It had been “gently” loved. The grand daughter was thrilled, and it has taken its place in the menagerie of creatures, foreign and domestic, wild and fabled, that fill her crowded bed. How that kid sleeps with all those animals is a mystery. Perhaps it is the nesting effect.

Like the unicorn, the piñata also has a multi-cultural history. The Chinese lay claim to the origin to a centuries-old whacking of the image of a cow filled with different types of seeds at the beginning of every New Year hoping for a favorable climate for their agriculture. Then the Aztecs say they invented the practice to honor the birthday of a god with a multi-syllabic name who needed appeasement—perhaps for every battered piñata there was one less human sacrifice. Once the Spanish monks moved into the Mesoamerica neighborhood, they immediately saw the opportunity to co-opt the ritual and created their own version of the tradition in the 14th century calling it “The Dance of the Piñata.” A seven-point piñata represented the seven deadly sins. The piñata itself represented evil, and the treats inside, the temptations of evil. The individual armed with a club was blindfolded to represent “blind faith,” then spun around before striking to represent the disorientation of temptation. When the participant struck at the piñata, it was the struggle against evil, and when a blow landed and the piñata broke open, the treats inside showered down upon the victor as a reward for keeping the faith. So these treats somehow magically turned from nuggets of temptation to a shower of blessing. Those tricky monks with their fluid theology. The things we humans do to placate the gods and ward off evil and entertain ourselves at the same time. Go figure.

But the one thing a piñata and a unicorn can do regardless of cultural claims to its origins is produce and give focus to a mob. As portrayed in the series of tapestries in Stirling Castle, the Scots were obsessed with the unicorn. According to the Scottish legend, the only reaction to “the other” was to kill or capture it. And as for the piñata, in our age of skepticism and technological high-mindedness, the only thing it inspires is the violent swings of a lethal cudgel at an inanimate object hung above the celebrants hankering after a treat. Both activities create what Eugene Peterson (author of “The Message” and other books), refers to as “the ecstasy of the crowd.” His reference is to something more primal and dangerous in our human psyche than any inspired emotion or worshipful experience shared communally.

The unicorn and piñata are historically connected to our family in a mystifying way. In celebration of the grand daughter’s birthday this year, the one who loves all-things unicorn, we gathered at her house for the party. Towering above the pile of gifts on the dining table was an appropriately birthday-themed unicorn piñata. After gorging on cake and ice cream, we moved outside where a passel of neighborhood kids, the median age being five years old, circled beneath the unicorn piñata suspended by the neck with a strong cord tied to a tree limb just out of reach of the kids but well within striking range. For the honor of the first swing, the birthday girl was handed a mini-Louisville Slugger. The cheering and whoo-hooing began, but alas, it was a swing-and-a-miss, so the bat was passed on to the next guest, and then on down the line. A blindfold would have made the game tortuously long given the participants’ level of skill, and had there been a traditional spinning of each child before they took their swing, it would have surely produced projectile vomiting in half the contestants given the amount of cake and ice cream consumed just moments earlier.

The cheering continued throughout the game as some swipes landed, but never a deathblow. Finally the birthday girl came to bat again (I lost count at how many times), and was given permission to swing until the unicorn piñata gave up the ghost and yielded its candied entrails. The oral clamor ramped up to the decibel level of a European soccer match—child, parent, and grand parent all contributing their vocal encouragement—bolstering the birthday girl into victory, and with one great and glorious swing, the belly of the unicorn burst open and the treats exploded into the air. And yes, the crowd went wild. It was a bacchanal for infants with sugary treats substituting for wine.

The kids scrambled for the sweet morsels: the older ones harvesting fistfuls and a few of the younger ones reduced to tears for their meager gathering of one or two treats. It was a kid-friendly yet extreme level of survival of the fittest. When it was over, the crowd moved back inside so the birthday girl could open her presents. The broken body of the unicorn was carried into the house, but its severed head remained attached to the cord and swung gently in the breeze. I wanted to remember this moment, and I was not sure why. It was such an odd feeling to witness, and yes, participate with a group of adults and kids in this human activity of destroying something in hopes of gaining something for ourselves or appeasing something outside of ourselves.

A mob of people can share a single-mindedness leading them to behave in certain ways that more often than not become destructive. I’m not a killjoy, I know how to have a good time, and I admit to the anthropomorphization of attacking the icon of a fairy-tale, but our actions of young and old alike did something to my soul. Peterson’s caution of the “ecstasy of the crowd” may go to the core of how we adults model our railings and actions toward things we do not understand or people we do not like or fear or disagree with to our offspring. We should not be surprised that our children are confused by such behaviors, and once their innocence is lost, can easily be led astray. The law of sowing and reaping is played out from generation to generation. We must be careful we do not sow the wind so as not to reap the whirlwind.

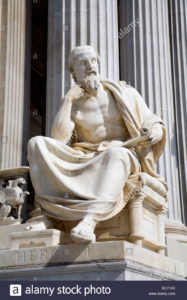

Cover Art: The Conquerors of the Bastille by Hippolyte Delaroche; 1789