David Compton: The Actor Who Could Play Anything

When you look someone in the eye, just look, holding the gaze or the glare, allowing the seconds to tick by, not speaking but studying in silence the shape of the face, the lines, the contours, yet always returning to the eyes, and being vulnerable enough to allow the observer of you to do likewise, can be as truthful and revelatory a moment as any person can have in their life. An actor is a truth-seeker. When an actor goes on stage, it is with the intention to look into the eyes of their opposite and not just speak the truth, but see it and draw it out in the other. When done well it is thrilling for the actors involved and riveting for an audience to watch.

Whoopi Goldberg said, “An actress can only play a woman. I’m an actor; I can play anything.” My dear friend, David Compton could play anything. I envied him. He made me jealous. I stole from him. I tried to detect falsehood when I watched him and always gave up after a few seconds. There were two roles for which I entertained the notion of auditioning when Nashville Repertory Theatre announced the auditions: The Old Man in “The Christmas Story” and the Emcee in “Cabaret.” What was I thinking? Who was I kidding? What reality was I trying to bend? David embodied those two roles, as in all roles he accepted, with a force that made each character he portrayed reach transcendence.

When he played Sherlock Holmes in Nashville Children’s Theatre’s production of “Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure,” my jaw dropped to the floor in those opening scenes and remained there for the entire performance. After multiple doses of Advil, I finally got the feeling back in my face.

I only saw him break character once, and it was my fault entirely. In “The Christmas Story,” David also was part of the Ensemble, and he played the old Schoolmarm. At the same time, I was in a production of “A Christmas Carol” playing Scrooge, a production that included Amanda Compton, David’s gifted and lovely wife. On a night off, I went to see “A Christmas Story,” and when David came out in his Schoolmarm dress and red wig and began to address the class, which included members of the

audience, he looked at me and began to berate me for misbehaving…a totally bogus charge. However, David was enjoying himself at my expense. He finished by asking me if I had anything to say for myself. I thought for a second and responded with, “Bah Humbug?” It took several beats for him to get control. It was pure joy for both of us.

In two rare acting combinations, David and I played bitterest enemies in one production and best friends in another. We were cast in Nashville Rep’s production of “To Kill a Mockingbird,” David as Bob Ewell and I as Atticus Finch. (It was also the first time I had the privilege to work with Amanda. She had stepped in to play Mayella Ewell in that last week of the run.) In the rehearsal process, we avoided the “spitting” moment in the play for as long as we could; that moment where Ewell spits in Atticus’ face after he humiliates Ewell on the stand during the trial. It was like rehearsing those kissing scenes that can make actors feel awkward at first. I needed to encourage David to let loose. Neither of us should fear the spray, I told him. It is a very intimate action for one human to spit on the other, and complete trust was required from both of us. David’s Bob Ewell was an astonishing and frightening specimen of a human being. At the time, he confessed that it took more of an emotional toll on him than any other character he had created to that point. Each Ewell/Atticus encounter throughout the play and throughout the run, made the hair on the back of neck crackle. He was electric.

In “Death of a Salesman” we played best of friends. In that first week of rehearsal my mother had died, so I was raw and unsure of myself. Rene Copeland and the cast and crew helped me carry my burden in a holy and unfathomable way that I still don’t have words to properly describe. There was one scene I dreaded above all, and that was the card scene between Willy and Charlie with Willy’s brother, Ben, joining in toward the end. That scene is like a trio in a Mozart opera where characters sing at cross-purposes with multiple stage actions taking place simultaneously. Charlie and Willy discuss troubles with work and children; Ben enters as imagined by Willy reminiscing about the past, all the while Charlie and Willy play cards. It is a brilliant mixture of psychological and emotional dimensions.

The mantra for the two of us in that scene was simple, “Keep it real.” The game Arthur Miller called for in the script was Casino. We researched the game, but found it so complicated that David and I just played a game of our own making, winning hands when specified in the script and when not. It became a beautiful, fluid moment ending in a shouting match, but setting up the two men’s final moment in the play when Willy comes to Charlie’s office to ask for money. They shout at each other once more, but Willy finally takes the money Charlie offers, and in a rare lucid moment before he exits, Willy says,” Charlie, you’re the only friend I’ve got. Isn’t that a remarkable thing?” The truth and honesty in that instant was achieved by two actors looking deeply into each other’s eyes all along the way.

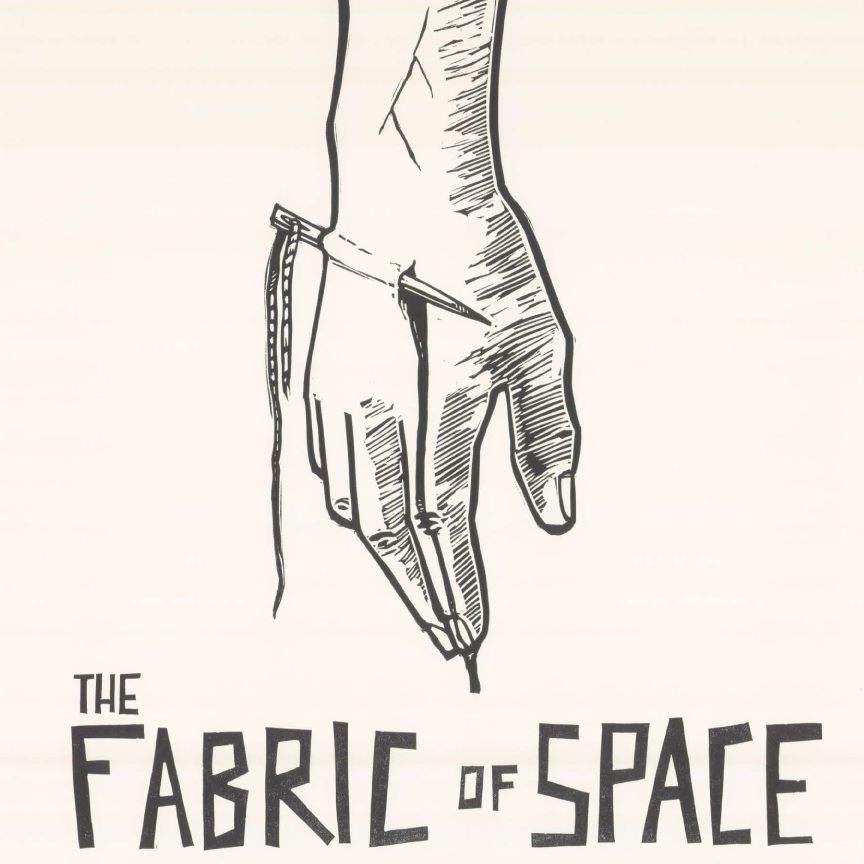

Between those two plays, David was the director for a play entitled “Stand” written by Jim Reyland. It is a powerful, two-character play about a man who befriends a homeless man and their journey of friendship. Barry Scott and I were cast in the roles. It was during that time David said something to me that I hold dearer than any other moment in our friendship and yet it haunts me. We were talking about age, he had turned fifty during this time, and after confessing my own age, I just laughed and told him he was just a “punk kid.” And with that big grin of his that always brightened up his face and illuminated any room, he said, “You know, I’ve always looked at you like a big brother.” In reality, I am a big brother to three younger siblings, but unbeknown to me till that moment, I had reached that symbolic status in David’s mind. And here is what haunts me: a big brother is supposed to take care of his younger siblings, try to keep them from harm. But my grip was not tight enough. He slipped through my fingers.

David was a master of capturing those ephemeral moments of honesty on and off the stage. He turned his eyes from nothing and fearlessly exposed the humanity in himself and everyone with whom he engaged. He never settled for second best, and he forced all of us who shared the stage with him to demand the best of ourselves. His body and soul had the ability to articulate the ineffable. He was a human bridge between truth and beauty. The last time I physically saw him at Skyline during his rehab, we made grand plans of getting back on stage together this next season, but he took an exit that was not written in the script we had imagined. My big-brother heart breaks because I was not watching close enough to warn him away from that exit. And now, like our good friend Scot Copeland who also left our Nashville theatre family way too soon, we must keep the light on for you, we shall always hold you in the center of our hearts, and we will forever be better artists and human beings because of your brief time among us upon this earth.

“Now cracks a noble heart. Goodnight, sweet prince; and flights of angels sing thee to thy rest.”