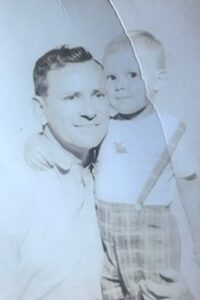

It is one of my earliest memories. I was four years old when I witnessed my father drinking, gambling, attempting a robbery, and then dying by his own hand from a knife thrust into his heart. I watched him die right before my eyes, and I had no ability to distinguish the degrees of the semblances of truth.

When Hamlet says, “…the play’s the thing / Wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the king,” he means that he will use a dramatic performance to test whether his uncle, Claudius, is guilty of murdering his father. And when Claudius sees the reenactment by the players, he flees the scene. When I saw the performance of my father’s death, I too fled the scene, whisked away in my mother’s arms, screaming.

Dad was playing the role of Billy Bigelow in the musical “Carousel.” Backstage after the show, I hurled myself into his arms sobbing in relief. That night Dad lay the instrument of his death on our dining room table; a rubber knife no longer than six or seven inches from blade tip to butt end. He even demonstrated how he used it.

This moment was a marvelous reality, one not fully explained or understood, nonetheless, irrefutably before me. I was an eyewitness to it all, and afterwards, I was tucked into bed by the one who had performed the feat. This was the mystery of storytelling, the story of my father, all-powerful, who could create such a wondrous illusion. My impressionable heart was frightened and awed by the experience of life, death, and resurrection. I did not know that these powerful themes would become foundational beliefs for life.