No, this story is not about an old-fashioned rocking chair Kay and I found in some small town antique shop. It is about my short-lived career as a rock ‘n roll star that began in a literal cave and ended when I found myself sitting on a picnic table between Robert Plant and Jimmy Page backstage of Municipal Auditorium during John Bonham’s drum solo. Have I gotten your attention?

Coming of age in the 1960’s, I had fantasies of being a rock star. I would bounce around in my bedroom in front of the mirror to The Who, or Jimi Hendrix, or The Rolling Stones, or (my secret confession), Paul Revere and the Raiders, playing these amazing licks on my father’s old tennis racket I used for a guitar. And I would visualize a sea of fans screaming their lungs out for me as they stormed the stage.

The memory of how our band came together is fuzzy. I was invited by Larry and Kenny Keaton to be the lead singer in this band. We were high school friends and they were excellent musicians. They played actual guitars, ones that required tuning, amplification, and skill. A drummer was added, and voila: a rock band was formed. The Keaton Brother’s decision to include me should have been questioned, but what I lacked in vocal ability, I made up in enthusiasm. I could belt a song, though perfect pitch was elusive, and I could dance. My religious upbringing frowned on such terpsichorean talent (Terpsichore, the Greek Muse of Dance), but I was not thinking of religion at the time, only the chance to create some rock ‘n roll. I had the moves if not quite the vocal chops.

We practiced way more than the offers to perform warranted. I remember a few basement parties, a middle-school hayride, and one pep rally. Talent scouts were noticeably absent. Our big moment came at a Battle of the Bands contest at Ruskin Cave in Dickson, Tennessee. The area was home to a late 19th century Utopian colony named for the English socialist writer, John Ruskin. The group had a short-lived existence, but the interior of the cave was the perfect place to set up a cannery operation for the Ruskin Colony. Like most utopias, they had a handful of active years before fizzling out. But that history was of little interest to me. I was only thinking of making rock ‘n roll history, inside a massive cave, no less.

No audition was required. You just showed up and signed up. Each band was given ten minutes to perform. There were covers of “Satisfaction” and “Light My Fire;” all fine songs, but by the tenth time of hearing it, all musical innovation had dissipated. No one was doing soul or funk, and we had worked up a killer version of “Shotgun,” by Jr. Walker & the All Stars. Even though we lacked a sax player, those Keaton Brothers could play a mean guitar and our drummer could beat out a funky syncopation that allowed me to do a choreographed reenactment of an old west shootout…me against the members of the band. The lyrics of the song had nothing to do with any historic shootout, e.g. the O.K. Corral, but we weren’t there to give a history lesson. We came in the name of rock ‘n roll in our matching blue shirts and jeans, black high-heeled boots with the pointy toes, and leather vests. Our hair was not long at the time. The school we attended, while they could not prohibit the spirit of rock ‘n roll from invading our souls, had the power to determine length of hair. It was the outward signs of belief that mattered, and short hair for the male was one sign of pious conformity.

While the other bands performed their three-song-set, we had prepared only one…a ten–minute version of “Shotgun;” and for me, it was my Isadora Duncan meets James Brown moment played to the hard-funk driving music. The choreography suggested the scene of the gunslinger standing against the forces of evil, and near the end of the song, I was riddled with bullets by my band mates. But after some funereal guitar licks and a drum solo, I was resurrected to new life, leapt to the microphone and belted out, “I said, Shotgun…shoot ‘em for he runs now.” The faithful would have considered it blasphemous to suggest that rock ‘n roll could raise someone from the dead, but we weren’t there to give theology lessons either.

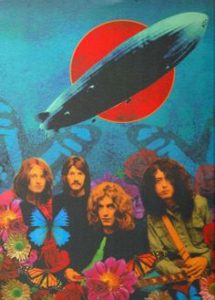

If my memory is correct—and suspicion should abound—I believe we took third place. But like the Utopian Ruskin Colony, the Battle of the Bands contest was the beginning and ending of my career in a rock ‘n roll band. However, I still bore the heart of a rock ‘n roller. I wore the black boots with the pointy toes until they were all shine and no sole. And, for a time, there was an emotional void to all rock music until I discovered Led Zeppelin. It was like listening to musical thunder and lightening; an all-powerful force with no gimmicks or cheap theatrics. Led Zeppelin was, is, and evermore shall be my rock band, my rock sound, my one true rock musical love.

The harmonic convergence of a Zeppelin concert at the Municipal Auditorium in Nashville and my unpaid internship for a musical variety show produced by a local television station was fortuitous. I was able to finagle an All Access pass from the television station on the condition that I would take pictures of the event. “Oh, yeah, sure, I’ll take pictures,” I said, and after the briefest of instruction from the station’s tech guy on how to use the requisitioned camera and a roll of film, I was sent to the concert. Understand, I don’t do technology…then or now.

The All Access laminate possessed all manner of magic, that and the camera hanging from my neck. I was able to float ahead of thousands of fans waiting in long lines, past the labyrinth of security barricades, and right into the backstage area where dozens of roadies were putting the final touches on all-things production.

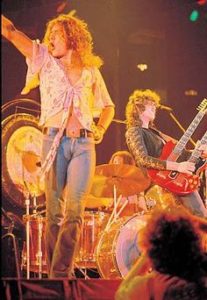

It was the loud screaming that caught my attention. I rushed out of the backstage area just as the black stretch limo was driving into the rear entrance of the auditorium. Police and security staff were restraining the hordes from rushing down the pedestrian ramps toward the limo. The mania only increased when the limo doors opened like multiple wings on a fierce, black dragon, and Jimmy, Robert, John Paul, and John and the Zeppelin entourage climbed out of the vehicle.

The band entered the “Employees Only” area behind the stage. It was the large break room for employees of Municipal Auditorium with a bank of lockers along one wall, bathrooms, kitchen area, and picnic tables for employees to eat their meals. I stood near the lockers and watched as the band breezed through the room and out into the holding area on the stage right side where Zeppelin’s Road Manager was engaged in a heated exchange with the city’s Fire Marshal regarding whether or not the houselights in the ceiling above the nose-bleed seating around the auditorium would remain on during the concert: Fire Marshal “On” (safety concerns) vs. Road Manager “Off” (aesthetic concerns). It was as if the band entered through the vomitory right on cue. If the lights did not go off, the band would return to the hotel and the Fire Marshal could explain to the ten thousand fans why they would be getting their money back. The promoter of the concert who stood to lose all that money saved the day with a compromise: as long as the fans remained in their seats and did not rush the stage (a common occurrence at rock concerts), the lights could remain off. The announcement was made, the lights went out, the band entered in the black and blasted into “Communication Breakdown,” and while the fans roared like a giant prehistoric beast, they dutifully remained in their seats.

With my magical All Access pass I was able to float around the stage area and between the metal railings set up in front of the stage. Once the music started, the first thing I did was to rip the filtered heads off of a couple of cigarettes and stuff them into my ears (a futile exercise that simply delayed the inevitable loss of hearing). Then I started snapping pictures. I had to at least act like I knew what I was doing.

I happened to be moving toward the break room when John Bonham began a twenty-minute drum solo (Bonham wasn’t called “The Beast” for nothing). Plant, Page, and Jones were exiting the stage and also headed for the break room. I thought I would be out of the way if I sat on top of one of the picnic tables and pretended to fiddle with my camera. To my surprise, Page slipped up on my right and sat on the end of the table and began to replace a broken string on his guitar. I was so nervous I could not have taken a picture at that moment even if my life depended on it. Page set the broken string between us and began restringing the guitar with a new one. Meanwhile, Plant took a seat on the bench on my left. I was the slice of Spam sandwiched between the reigning lords of rock ‘n roll and “acting” cool was the severest test thus far of my limited talent.

“I wish I had a joint right now,” Page said as he tightened the new string.

I could not fulfill that request, but I did fumble the cigarette pack out of my shirt pocket and offered him one. He pondered it for the poor substitute it was, but decided to take it anyway. He and the others were then summoned back to the stage by the stage manager, and as Page scooted off the table, he left behind the broken guitar string. I asked if he wanted it and he simply shook his head. As the trio exited the break room, I snatched the string off the table and stuffed it into my pocket.

By the encore, the crowd could no longer contain themselves and rushed the stage. As a consequence, all the lights in the auditorium were turned on and the last song they played was in light bright enough to cause retina damage. A week later I was told by the tech guy at the television station that I neglected to wind the film forward after each shot. There were multiple exposures on one frame that proved worthless…like I said, not tech savvy. I reverently placed my guitar string on my bookshelf at home, but my mother confessed that when she found it in the room one day while cleaning she thought it was “just an old wire” and threw it into the trash. We weren’t communicating well back in those days.

And now, decades later, in my secret moments when Kay has left the house, this aging rocker will get the broom out of the closet, insert my double CD of Zeppelin’s greatest hits into the stereo, cue the “Whole Lotta Love” track, and turn the volume “up to eleven,” (as Nigel Tufnel so eloquently explained), and…wait for it…wait for it…, burst into: “You need coolin’…Baby, I’m not foolin’/Gonna send you back to schoolin’…I’m gonna give you my love….Want a whole lotta love.” Now who would not storm the stage at the sound of that legendary rock ‘n roll music?