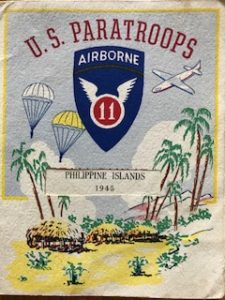

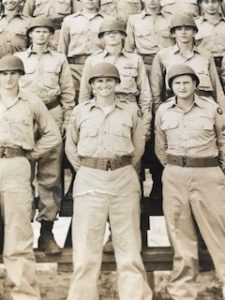

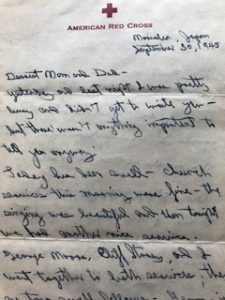

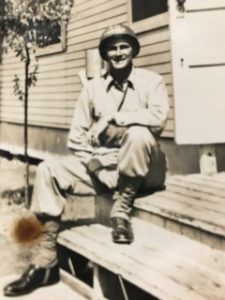

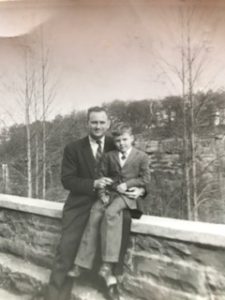

How does a father teach a son to be a man? What is it to even be a man…to be a father…to be a son? In 1944, Dad ran away from home at the age of seventeen, hitchhiked from Richmond, Virginia all the way to Ft. Lauderdale, spent a few nights on a park bench, lied about his age to the Army recruiting officer, worked as a bellhop in a swanky hotel until he was inducted into the Army. Somewhere in that time-frame between bellhop and paratrooper, Dad called his parents and told them what he had done. In part, it was his parent’s fault. Sunday after Sunday, “solider-boys” home on leave were invited to lunch after church at my grandparent’s table. The stories these young men told of war and honor inspired my young father’s imagination. After basic training Dad was shipped off to the Philippines to fight.

The process of “Know Thyself” began before Dad ran away from home. He had suffered a few blackout spells as a kid, and the doctor had cautioned against overexertion. He could have had a medical deferment for his unreliable heart, that fact, plus being an only child, would have kept him out of the military, but then Dad would never have had his personal odyssey, an adventure he pondered for some time. He had run away in his mind long before he slipped out the door when his parents weren’t looking. My father understood who he was and dreamed of what he might become, then made the bold choice to defy his overprotective father and mother.

I ran away from home a few times myself, but it was because I was being a selfish jerk, not for such a grand reason as serving in a World War. I lied to my parents often, but ten times out of ten, it was to keep from getting caught in some misbehavior. The nobility gene had failed to pass from my father to his firstborn son. I know Dad often looked at me and wondered what he had spawned. But that is the way of fathers…to look upon their offspring and wonder…to wonder at many things.

I remember an early point of wonder at my father when I was a child of seven or so. In the basement of my grandparent’s pre-Civil War house in Richmond, my grand mother had set up her one-woman seamstress shop. Her skill at designing and creating women’s clothing helped the family survive the Depression. The steps down to the basement were off of the kitchen. I was in the kitchen and could hear a heated conversation coming from below. It was my father’s voice arguing with his parents. I don’t think I had ever heard this type of verbal exchange between them, and it frightened me. But instead of dashing away, I slipped quietly down the basement steps to eavesdrop.

The gist of the argument was the inequality of the black and white races. Dad’s parents were committed to the old South viewpoint even citing the Bible (a book both parties were devoted to), as a basis for their belief. With equal fervor, Dad came back at them with counter arguments that not only included a scriptural foundation, but also a civil and constitutional one. I peeked around the corner into the shop and saw my mother sitting in a chair with tears streaming down her face. I cannot remember the exact words. I just remember that my father refused to back down and that my mother sat there refusing to leave supporting her husband’s position. What a wonder for a seven-year-old kid to listen to his father stand up to his parents. He could have run away. He had done it before, but he stood his ground, and the entrenched, generational racism on my father’s side of the family suffered a serious blow that day.

Then there was the time in the mid 1960’s when my father was responsible for promoting and producing the recital of a renowned opera singer for a citywide event. She had brought her African-American accompanist. After the recital when the local press was gathering for the photo opts, a very powerful man in the community wanted his picture with Dad and the opera singer. He told my father under his breath, “…But no picture with the (pejorative term).” Once again my father refused to back down and the accompanist rounded out the quartet for the photo shoot. The power of the powerful man was deflated that night. Dad had jumped out of airplanes and was shot at by a fierce enemy in war. The threats of this man were hollow. What a wonder to ponder!

Then there was the time in the late 1980’s when HIV was becoming epidemic and the organization, Nashville Cares, was working feverishly to help victims of the disease. Dad volunteered to drive patients whose family or friends were unavailable, to and from doctor visits and hospital stays. Kay and I and our girls had recently moved back from Los Angeles. Dad was in the middle of final dress rehearsals for a play he was directing and asked if I would transport his latest charge back home. (Yes, the theater stops for no man) I drove over to the house to discover two things: 1) the young man had slept in my old room in my old bed the night before, and 2) the young man lived in a rural area a couple of hours away.

If I had been a better person, I would have welcomed my father’s invitation into his expansive and inclusive world of serving “the stranger.” You know, that “I was a stranger and you took me in; I was sick and you looked after me,” behavior that Jesus encouraged. But I was grumpy and a little scared at the unknowns. There was too much mythology surrounding HIV at the time for me to feel completely comfortable with performing my duty for the stranger. But I drove, and the stranger and I talked, and I gradually became less grumpy and a little more appreciative of how I was spending my day.

The stranger did indeed live in rural America, in a commune in the woods with several others who also suffered the ill-effects of HIV. The large cabin was located a couple of miles off a poorly paved back road that became a dirt road more suited for a four-wheel-drive vehicle with a reinforced wheelbase. We pulled in front of the wooden structure he called home, and I asked if he needed help, but he declined. When he opened the door to enter the house, I heard weak but enthusiastic cheering at his return. Here, at least, he was not a stranger. I was the stranger. Death by disease held no fear for my father, not after having seen the death of comrade and enemy alike in war. I wonder how many “strangers” of all shapes and sizes and colors, conditions of health, in all sorts of dire straights that my father served in his lifetime. I wonder, and I marvel.

Elie Wiesel said in an interview once regarding his father/son relationship, “If you don’t know me you can never know yourself.” Two nights after Dad died I was sleeping in my old bed in my old room. We were in the midst of the wonderful chaos of family and friends sharing our grief and celebrating a life well lived and it was easier to stay at home with Mom. That night, Dad appeared to me in a dream. He walked into the bedroom, and I sat up with a start. He was wearing his Army dress uniform with a chest full of metals. He was smiling…when was he not smiling…, and he sat down on the foot of the bed. He looked at me, gave my legs a gentle slap, and said, “Son, you’re gonna be just fine.” Perhaps I went to sleep a boy and woke up a man.

Dad was a teacher at heart. Thousands of students passed in and out of his classrooms, rehearsal halls, and performance stages. If they were paying attention, they were able to glean from his knowledge and skills as a music and theater artist. But for me, he taught by doing. When I was paying attention, I began to know myself and my skills at becoming a man and eventually a father slowly improved. I wish I had paid more attention. If running away from home helped produce the kind of man my father became, then I can say I am the proud child of a teenage runaway. Oh, the wonder of fatherhood and the miracle of manhood!