When my doctor of thirty years retired (how dare he), I recently was breaking-in a new doctor and suffering through the process of filling out multiple forms as if I were applying for some high-powered job. I was asked by a perky med-tech if I had ever smoked. The tech could have read my written answer on page three of the six-page form, but no, a verbal response was required. “How long did you smoke, and when did you quit?” was the question. “Started in earnest in 1967 and quit in earnest in 1974.” Then I sighed and lamented, “But there isn’t a day since that I don’t crave a smoke.”

“Oh, when I quit it was the easiest thing,” said the tech. “And I have never had a craving.” The tech must have never inhaled or ever heard Mark Twain’s quote, “Giving up smoking is the easiest thing in the world. I know because I’ve done it thousands of times.”

My first encounter with cigarettes was at the tender age of nine. My best friend at the time was the same age. His mother was a single mom and a smoker. The sordid events surrounding her single mom status was more of a theological sticky wicket in our religious circle than the fact that she smoked, but my folks were more open-minded on such matters, so whenever I was invited to go home after church with my friend and spend the afternoon between morning and evening services—the bookends of our every Sunday—I was given permission. During church one morning, my friend and I, along with a few other contemporaries, sat together in a separate pew away from the adults but still within the clear view of the parents were it necessary for any of them to use the clearing-of-the-throat reprimand at the first sign of squirming during the tedium of the service.

Before I got my first job as a paperboy and could tithe from my own income, I was always given a quarter each Sunday to drop in the collection plate. On this Sunday it had been prearranged that I was going home with my friend. So when the ushers started coming down the aisles with the collection plates, my friend whispered into my ear, “Keep your quarter. We’ll buy cigarettes with it later.”

Funny how sin and temptation always starts in the church pew. How was I going to pull this one off? Like God, my mother was always watching. But I suddenly had an idea that was sure to fool heaven and earth. I secured the quarter between two fingers, cupping my hand to conceal the twenty-five cent piece, and when the plate came down our pew, I waved my hand over it as if dropping my offering into the plate before passing it down the row. Mother smiled, and I tucked my quarter inside my sweaty palm until she looked away and I could slip it into my pocket. With such slight-of-hand skills I could have become a magician.

My friend lived next to a drugstore, and after lunch, the two of us went outside to play…ostensibly. I always liked going over to his house because his mom’s supervision was lax, which meant we could get away with some mischief that more observant parents would kibosh, like smoking cigarettes behind the garage. As we ambled over to the drugstore I reached into my pocket and pulled out my quarter purloined from God. I instantly felt guilty. The money entrusted to me by my parents for an offering was about to be spent on tobacco. My nine-year-old brain could not come up with any amoral rationalization for my actions, but I was committed to the deed and would see it through. The grip of sin was cold and hard on my young mind and heart.

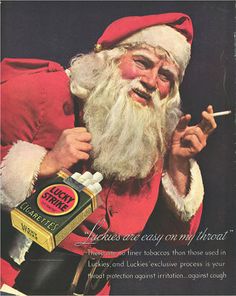

Since I had never bought a pack of cigarettes in my life I had to entrust the purchase to my more experienced companion. He had made frequent trips to the drugstore, “cigarette runs,” he called them, for his mother. My mother would often send me on “milk and bread runs” to our local grocery store, so this “run” was my first. When we entered the drugstore, right in front of the cash register were racks and stacks of cigarette packs all within reach of our fingertips. I was dazzled by the colors and images on the advertisement posters of the various brands: masculine men, glamorous women in masculine and glamorous poses, even a picture of Santa Claus enjoying a Lucky Strike while delivering presents. We were years away from the Surgeon General’s report that proclaimed tobacco nicotiana was hazardous to one’s health. Every face on these advertisements was smiling and happy; no grim, cancer-riddled images of the diseased to be found.

Now one would think that the person behind the counter might be suspicious of two nine-year-old boys plopping their quarters on top of the glass counter and asking for two packs of Lucky Strikes (I mean, if the brand was good enough for Santa, right?), but this was “back in the day,” a more innocent era. Besides my friend had the perfect line, “Picking up a couple of packs for my mother.” Two quarters. Two packs of cigarettes with two boxes of wooden matches in one small brown bag. One for the mom. One for the boys, and out the door we went. My friend removed our pack of cigarettes and matches from the bag concealing them under his shirt before entering the house. We handed off the other pack, and the mom nestled into her easy chair with a newspaper, cup of coffee, and a pack Lucky Strikes to occupy her afternoon.

My friend and I headed straight for the backyard and slipped behind the garage. The process was magical like a Japanese tea ceremony: tapping the pack a couple of times on the back of your hand to tamp down any loose tobacco in the cigarettes, pulling the red-colored cellophane tab around the circumference of the pack, stripping off the silver paper on one side of the official seal, tapping out a couple of cigarettes so they stuck out like smokestacks, being offered a cigarette (from one “masculine man” to another), and placing the filtered end into your mouth. Those few seconds before lighting up when that cylinder dangled from my lips was the moment I began to shed the skin of childhood. And then the lighting of the match: the scratchy sound of match head striking across the flinty board on the matchbox, the hissing of burning sulfurs, raising the fire to the tip of my Lucky Strike inside a cupped hand and sucking in the flame. I was transformed into Prometheus stealing fire from the gods.

Three cigarettes consumed and my joy turned to sorrow. The gods had sent the eagle to feast upon my liver. My head detached from my neck. There was a tingling in my extremities. My eyes began to water. I crawled a short distance on all fours, but my muscles had become like jelly. And then my stomach started to boil and the hurling began. I don’t remember the rest of the afternoon. I don’t remember going to church service that night. I don’t remember coming home. What I do remember is entering my parent’s bedroom after my siblings were asleep and bursting into tears while confessing all that I had done that day. My first cigarette led to my first confession.

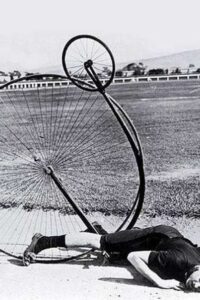

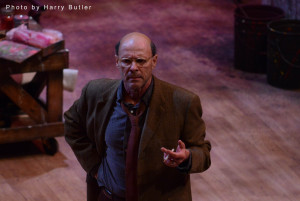

While my initial experience at smoking was traumatic, the memory did not prove a deterrent to my future seven-year addiction. And yes, I’m glad I quit, no regrets, but I do miss it, and I do get the craving from time to time. When I played the character of Mark Rothko in “Red” for Nashville Repertory Theatre, I smoked during each performance. Rothko was a chain smoker. One night after a show a patron told me that I “smoked like a professional.” I told him that the technique of lighting up a cigarette and smoking it down to the stub while going about your business was, for me, like getting on a bicycle after a long absence. One never forgets the mechanics or the joy of each drag.

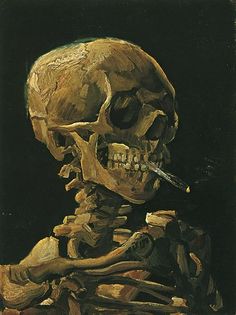

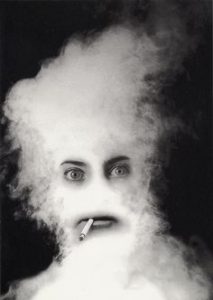

Some might hold to the opinion of King James I of England that, “Smoking is a custom loathsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain, dangerous to the lungs, and in the black, stinking fume thereof nearest resembling the horrible Stygian smoke of the pit that is bottomless.” On the contrary, when I get to heaven, after thanking the good Lord for making it possible for me to gain entrance and after greeting those who have gone before, I will quietly ask one of the angels for directions to the smoking section. I will light up my first cigarette in decades, and I will inhale so deep that the smoke will flow down to my toes. Now that’s heaven.