It is a wondrous thing what self-discoveries are made within the human heart when a layer of innocence is lost. A dramatic experience may destroy a belief system but make way for new wisdom. From 1959-1961 we lived in Bloomington, Indiana while Dad was completing his doctoral course work in choral music at Indiana University. Until that year, I had been in a private school environment (K-third grade), and was suddenly thrust into the culturally broader world of public education and living in diverse, multi-dwelling housing complexes instead of a single family home. In an earlier post, I have written a different story of that time entitled “Blood Brothers.” It chronicles my friendship with Raymond, one of three best friends I had during that two-year period, and a lesson in courage my blood brother taught me.

The other two boys were Eran from Israel and George from Sweden. We were a crew. Our fathers were all doctoral candidates at Indiana University in various fields of study. We lived in University housing, though Eran and George lived in the newer, more spacious family apartments while we lived in the cramped, renovated army barracks. We attended Fairview Elementary public school together.

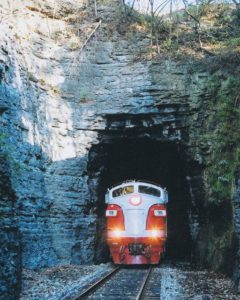

What I may have lacked in residential amenities enjoyed by my friends, I made up for by having easy access to a recreational area like no other. Less than one hundred yards from our barrack apartment building was a railroad track that cut through a hill leaving jagged, thirty-foot cliffs on either side then went under a bridge at the highest point of the terrain. Eran and George happily abandoned the man-made, state-of-the-art play sets built for their apartment complexes for the more life and limb threats of cliffs and woods and trains.

What I may have lacked in residential amenities enjoyed by my friends, I made up for by having easy access to a recreational area like no other. Less than one hundred yards from our barrack apartment building was a railroad track that cut through a hill leaving jagged, thirty-foot cliffs on either side then went under a bridge at the highest point of the terrain. Eran and George happily abandoned the man-made, state-of-the-art play sets built for their apartment complexes for the more life and limb threats of cliffs and woods and trains.

There was nothing cooler in the world than to be playing on the tracks, hear the whistle of a train, and see the Cyclops-beam of the headlight making its circular pattern in the snout of the engine as it headed toward us. The yards were not far away, so a train was either slowing down coming into the yard or building speed as it departed. Either way, you had a minute or two to get off the track and scale the jagged cliff sides to a safe perch. We three would scream at the top of our lungs as the trains rumbled by and would toss Osage oranges at the cars, pumping our arms in the air with delight as the pulpy, inedible fruit exploded against the steel walls and rooftops. What a playground. And yes, this was back-in-the-day before the trend of “parenting” had taken over our modern culture.

Outsiders that we were, it did not take long for the three of us to make enemies with some of our older schoolmates at Fairview Elementary. One Saturday, a gang of four or five boys from a neighborhood near our school rode their bikes into the section of University housing where I lived. My mother was hanging laundry onto the clothesline next to our building when I saw them coasting down the road like mini-Hell’s Angels heading in my direction. They had not ridden over to see if I could come out to play. They began to taunt me hurling profane insults at my manhood, no doubt inspired by my hiding behind my mother’s skirts. Hell hath no fury like a mother protecting her child, and Mom verbally ran roughshod over those boys and sent them into retreat. But I knew that Mom’s threats had not brought true repentance in the hearts of the gang members. Their departing laughter at my obvious spinelessness meant a future day of reckoning when a mother’s protection was not available. Their superior numbers could only bolster enough courage that an individual could never summon.

Not long after this incident, late one afternoon, Eran, George, and I were walking the tracks engaged in our latest adventure. The three of us saw nothing unusual about the international nature of our friendship. It had no significance to us. We enjoyed each other’s company. We went to the same school, rode the same bus, lived in University campus housing, and all spoke with funny accents. The main aspect of our commonality was a shared, near-mystical imagination. With cliffs and woods and railroad tracks and massive columns supporting the bridge with open areas underneath as our expansive playground, we could conjure any scenario that required three heroes to right all wrongs.

As we moved along the tracks, we had no idea we were being watched from the cliffs and woods above us. It was not until Eran yelled in surprise and raised his hand to his forehead that we realized we were under attack. Blood began to flow through Eran’s fingers and down his face. The three of us threw ourselves against the cliff wall, providing us protection and allowing a moment to plot a strategy.

We could have raced down the tracks to try and outrun the rocky missiles. We could just wait it out and let the coming darkness cover our escape. We could hope for a parental search party to come rescue us. Or we could “take the hill.” In this momentary lull, the gang began to hurl racist insults directed mostly at Eran for having escaped the Nazis, and at George and me for being friends with a Jew. We were only ten years old and it had been fifteen years since the end of World War II. Through this profane and shaky grasp of history, I was getting a one-sided view of the recent past that I did not know how to process. At that moment, I cared nothing about history. We had been ambushed, and my best friend was bleeding from his forehead as a result.

I ignored my “turn the other cheek and pray for your enemies” doctrine encouraged by my religious persuasion for the more visceral “vengeance is mine” response. The gang may have had the higher ground, but they were in our territory, and we knew all the paths and crevices that cut through the cliffs to the woods on top. I jumped onto the tracks waving my arms and instantly put to good use all my experience gained from playing dodge ball as the rocks hailed down upon me.

Eran and George used this distraction to grab fists full of rocks before they charged up a steep path concealed inside the cliff wall. I followed right behind, my own expanded fingers dripping with an excess of rocks. The gang had not expected this counter attack and was surprised by our sudden appearance at the top of the cliff. George unleashed a mad scream and both handfuls of rocks, one volley after another, sending the gang scrambling through the woods. Eran hit one of the fleeing ambushers in his side, and I succeeded in hitting another in his leg. Once we had unloaded our ordinance, we stood still, our lungs panting for air, and watched as the gang made it to the clearing, hopped onto their bikes, and raced away.

There were no triumphant war hoops or victory dances, not even self-satisfied slaps on the back, which we often performed after one of our fantasized adventures. This was no fantasy. This was real, and there was blood to prove it. We decided to make our explanation of Eran’s gash on his forehead simple: he slipped while scaling the cliff and hit his head. We could stick with that story even under intense, parental interrogation. In the short time the three of us were friends, I don’t remember ever discussing the horrors of the Holocaust and how it might have affected Eran and his extended family, but I know that afternoon on the railroad tracks was my personal introduction to racial bigotry and how it can violently manifest itself in human action.

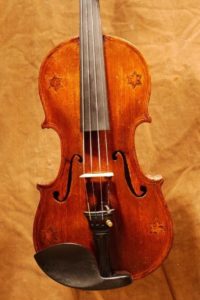

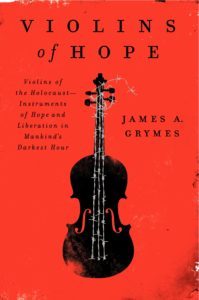

“The Violins of Hope,” is a traveling exhibit of several violins used by Jewish musicians who survived the Concentration Camps by playing in small orchestras. “We played music for sheer survival,” explained Heinz Schumann, one of the orchestra members at Auschwitz. “We made music in hell.” These instruments have survived concentration camps, pogroms and many long journeys to tell remarkable stories of injustice, suffering, resilience and survival and are currently on display at the Downtown Public Library in Nashville through May 27, 2018.

“The Violins of Hope,” is a traveling exhibit of several violins used by Jewish musicians who survived the Concentration Camps by playing in small orchestras. “We played music for sheer survival,” explained Heinz Schumann, one of the orchestra members at Auschwitz. “We made music in hell.” These instruments have survived concentration camps, pogroms and many long journeys to tell remarkable stories of injustice, suffering, resilience and survival and are currently on display at the Downtown Public Library in Nashville through May 27, 2018.

Elie Wiesel wrote in his autobiography “Night” of an experience he had listening to a musician he knew only as Juliek play a Beethoven concerto on his violin in a packed barrack in Auschwitz. “Never before had I heard such a beautiful sound. In such silence,” Wiesel wrote. “All I could hear was the violin, and it was as if Juliek’s soul had become his bow. He was playing his life. His whole being was gliding over the strings. His unfulfilled hopes. His charred past, his extinguished future. He played that which he would never play again.” The next day Wiesel found Juliek’s lifeless body next to his crushed violin.

On May 26, 2018 at 3:00 p.m., at the Nashville Downtown Public Library, I, along with other actors from Nashville Repertory Theatre, will perform selected dramatic readings of the stories collected from the book of the same title of how these instruments were rescued, repaired, and eventually given a second chance to make the beautiful music they were created to play. Two musicians from the Nashville Symphony Orchestra will also play these instruments. The event is free and open to the public.

While my brief coming-of-age experience cannot compare with Wiesel’s, I will always remember Eran and George and our defiant moment on the railroad tracks. But more importantly, I have learned over the years that during a malevolent time, it is always best to create something beautiful. Beauty is the best defiance.

Cover Art: Violin by Yaakov Zimmerman