The Arnold kids were never given financial allowances growing up. My parents did not have that kind of disposable income. If we wanted to have spending money we needed to make it. So at the age of ten how I came by the exorbitant sum of a few dollars to purchase the blue-beaded necklace for my mother on Mother’s Day was probably from scouring parking lots and playgrounds for lost change. Our family had relocated to Bloomington, Indiana so Dad could get his doctorate in choral music at Indiana University. We lived in old Army barracks converted into housing for those students attending the University with their families. There were eight two-bedroom apartments, and the landlord warned emphatically that should a building catch fire, “Just grab your kids and run, because the whole place will be up in flames in fourteen minutes.” I’m not sure how he knew that fact, but for that two-year residency, our noses were always on the alert for the smell of smoke.

The purchase of this necklace was the first time I was proactive in getting something for my mother without the aid and support of my father. With my pockets stuffed with coins, I peddled my bicycle over the railroad tracks behind our apartment building to a little shopping area where the store was located (a five-and-dime, not a Jared), and returned a successful “hunter/gatherer” with my prize in a paper sack. Mom wore it proudly to church that Mother’s Day Sunday, and countless other times. I was told often that this necklace was the favorite piece of jewelry in her collection, and for a time I believed that my offering trumped her wedding rings, fake pearl ensembles, and broaches embedded with imitation gems. When Mom died in 2015, my sister, Nan, was in charge of dispersing Mom’s jewelry collection, and the first thing she located was the blue necklace and returned it to the “giver.”

Presenting Mom with the necklace that Mother’s Day brought tears to her eyes, a reaction I continued to induce for years to come though rarely for such sentimental reasons. Isn’t that what sons are supposed to do to their mothers? Make them cry often? If so, I kept pace with the average and most likely exceeded the allotment of times a son is supposed to make his mother cry. Those weepy occasions began to taper off when I married Kay. I think Mom’s quote to my bride on our wedding day was something to the effect of, “I’m handing him off to you. I did the best I could.” In the long march to my wedding day, before the “handing off,” Mom said that she had long ago given up praying that I would have good friends or get through high school and then college or just go to church once in a while. She finally resorted to begging God to just keep me alive…at least until she could find someone else to take over. I know, poor Kay.

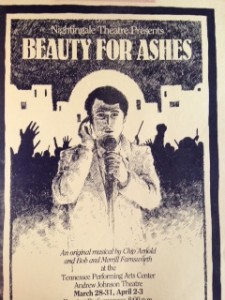

A big turnaround in our relationship came in 1972 when Mom and I were cast in “Dollars to Doughnuts,” a very forgettable comedy produced at the Barn Dinner Theatre. While my mother had done several plays in her life, most of them opposite my dad, it was the only play my mother and I did together. I did direct her in a film sequence that was inserted into the live performances of a musical I co-wrote with Bob and Merrill Farnsworth entitled “Beauty for Ashes.” The musical was a modern retelling of the Passion Week of Christ, and in the filmed vignette, Mom played the Virgin Mary reminiscing to the television interviewer about that fateful night in the stable in Bethlehem when she gave birth to the Son of God. She found my casting choice at once intimidating and hilarious. “I’m no virgin,” she quickly said when I asked her to do the role, which made me groan and plug my ears because I certainly didn’t want to know about any of that.

The Barn Dinner Theatre experience was a concentrated six-week period of mother/son time devoted to one purpose: our combined incomes for that job went to pay my college tuition. The weekly actor’s salary from the Barn was paltry at best, but we could boost our nightly take-home with the tips we received by waiting tables before the show. After two weeks of rehearsal, we opened the play, and for the next month, six days a week we drove together out to the Barn, set up the tables, served our customers with a smile, put on a show, and drove home late that night. No matter how exhausted we might be when we got home, we’d count up our tip money-her take invariably exceeding mine-and stashed the amount in a cigar box she kept in her dresser. At the end of the “Doughnut” run the combined total of salary plus tips was deposited into the bank and a check written to the academic institution. One could say “easy-come/easy-go,” but it did not come easy and it certainly did not go easy.

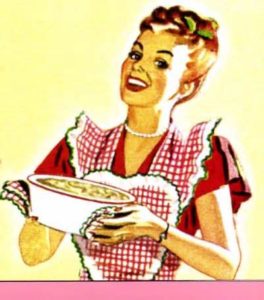

During the run of the Barn show I watched my mother serve the patrons at her assigned tables with a grace and dignity that I also witnessed at home as a partner with Dad hosting the populations of guests that flowed in and out our front door. And our mother/son chats riding back and forth from the theatre were transforming into peer-to-peer conversations. Dare I say that a friendship was beginning to bud that included mutual respect for personal motivations and life choices? I think so. Mom was a devoted wife, a mother of four children, the Food Editor for the Nashville Tennessean, and here she was taking the time to wait tables and put on a show with and for her firstborn. Such a mother’s devotion was worthy of wearing the Crown Jewels, which we saw together in London many years later, and to which she commented while staring into the glass-encased, multi-million-dollar exhibit, “I wouldn’t trade any of those jewels for my blue necklace.”

During the run of the Barn show I watched my mother serve the patrons at her assigned tables with a grace and dignity that I also witnessed at home as a partner with Dad hosting the populations of guests that flowed in and out our front door. And our mother/son chats riding back and forth from the theatre were transforming into peer-to-peer conversations. Dare I say that a friendship was beginning to bud that included mutual respect for personal motivations and life choices? I think so. Mom was a devoted wife, a mother of four children, the Food Editor for the Nashville Tennessean, and here she was taking the time to wait tables and put on a show with and for her firstborn. Such a mother’s devotion was worthy of wearing the Crown Jewels, which we saw together in London many years later, and to which she commented while staring into the glass-encased, multi-million-dollar exhibit, “I wouldn’t trade any of those jewels for my blue necklace.”

Mom was so ahead of her time. She could have been a poster girl for the Women’s Movement though she never marched or protested…not that there’s anything wrong with that. She knew how to stretch a hard-earned dollar for a family of six while winning prizes and honors for her work as a culinary journalist. Yes, I made my mother cry more times than I like to remember, but I lived long enough—surely because of her prayers—to regret doing so and eventually develop the conviction to beg her pardon, and, from time to time, have the opportunity to make her proud to have brought me into this world. She said she was never more proud than when she watched me on stage. But I found that to be a dubious claim. My last two plays she attended she sat on the front rows and slept through most of each performance, or perhaps it was just during my scenes. I’m sure the cause was sleep deprivation from all those years of lying in bed and praying that every siren she heard in the middle of the night was not an ambulance carrying her son to the emergency room.

So here’s to the memory of Bernie-Laurie Wyckoff Arnold on this Mother’s Day. Laughter and joy have replaced the tears, and she has exchanged her blue necklace for a heavenly crown.