When Kay and I traveled to Italy a few years ago one of our favorite experiences was in Assisi. We had come from a couple of days in Sienna and had booked a hotel online the day before we arrived only to find out when we got to the location that the hotel was closed for renovation. In profuse, broken English the manager apologized for the website’s misinformation, and helped book another hotel. Assisi is a walled city built on a hill overlooking the valley. The city center is restricted to only pedestrians. We could drive to our hotel about halfway up the steep incline but could venture no farther by car. We checked in, threw our luggage in the room, and headed out.

Just across the narrow street stood a man in front of his shop which specialized in olive oil, balsamic vinegar, and wines from local presses and vineyards. He waved us over, and for the next twenty minutes in manageable English, gave us the history of olive oil in the region and why the brands he carried were the best. He insisted we taste some of the finer selections of olive oil and balsamic vinegar. This was not like the wine tasting experiences we have had in other parts of the world. After only a few “tastes” we excused ourselves and hurried away. Before we could enjoy the sights of Assisi we had to stop at a pharmacy for some antacids to quiet our grumbling stomachs. A more refined palate might have enjoyed the subtle differences in the selections of olive oil and balsamic vinegar, but for my taste buds, only vintage wines were in order for the rest of our travels.

Eight hundred years before, St. Francis lived in this city. As a young man he had a privileged life. His father, Pietro, was a wealthy merchant providing expensive material and fabrics to the medieval equivalents of Dior, Klein, and Cardin. And his mother, Pica, belonged to a noble family from Provence, France. This prosperity allowed his parents to indulge the whims of their son. One biographer referred to Francis as the “king of frolic” who surrounded himself with other young nobles indulging in every kind of debauchery. He was a quintessential party animal, not yet the hallowed saint of paintings, literature, and films preaching to animals, kissing lepers, and taking “Lady Poverty” as a wife. His early lifestyle did not foreshadow an inclination to follow in his father’s career let alone a holy calling. The world of the youthful Francis was in turmoil; conflicts between church and state, battles between Assisi and the surrounding towns, and hostile political and economic spats between the local classes. For us human beings there is nothing new under the sun.

Eight hundred years before, St. Francis lived in this city. As a young man he had a privileged life. His father, Pietro, was a wealthy merchant providing expensive material and fabrics to the medieval equivalents of Dior, Klein, and Cardin. And his mother, Pica, belonged to a noble family from Provence, France. This prosperity allowed his parents to indulge the whims of their son. One biographer referred to Francis as the “king of frolic” who surrounded himself with other young nobles indulging in every kind of debauchery. He was a quintessential party animal, not yet the hallowed saint of paintings, literature, and films preaching to animals, kissing lepers, and taking “Lady Poverty” as a wife. His early lifestyle did not foreshadow an inclination to follow in his father’s career let alone a holy calling. The world of the youthful Francis was in turmoil; conflicts between church and state, battles between Assisi and the surrounding towns, and hostile political and economic spats between the local classes. For us human beings there is nothing new under the sun.

Francis’ carousing did not leave much time for academics, nor was he particularly interested in education. He aspired to be a knight of Assisi. He could afford the clothes and armor. In one of the many skirmishes between rival city-states, Francis was captured and held for ransom after a battle with citizens from Perugia. When it came to war, being of noble birth gave one an advantage. If captured, one might be chained in a dank dungeon, but one stayed alive and eventually released when ransom was paid. While the common citizen-soldier either died in battle or had their head lopped off by the victor. While in captivity Francis became ill and in that period began to contemplate a different life. Once liberated he returned home and rejoined his friends, but their partying had lost its appeal. His heart was gradually changing. He found he was drawn to a more spiritual life. His focus shifted from revels with friends to those less fortunate. Biographers have recorded several experiences that are attributed to Francis’ change of heart, some factual, some expanding into legend, but one experience seems to be authentic: a confrontation with his father in the city square in front of the basilica before a crowd of people.

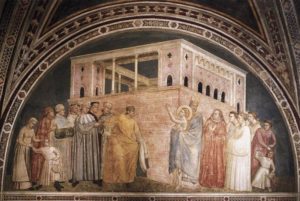

As I stood in the area where the confrontation took place, I could not help but imagine the scene. Francis was becoming more disinterested in money much to the consternation of his father. He stood to inherit a large sum from his mother’s side of the family, funds his father could use to expand the business, but if his son was not going to follow in the family trade, instead, spend his time in benevolent work and prayer and giving away his wealth, then drastic measures were needed. After learning that Francis had taken fabric from his shop, sold it, and given it to the church, a furious Pietro dragged Francis before the bishop and demanded he return the money and renounce his rights as heir to the family fortune.

Imagine standing in the midst of a crowd of curious onlookers watching a father berate and denounce his son, threatening him with an ultimatum that both father and son might regret for the rest of their lives. No one could have anticipated what happened next. Francis began to remove his clothes and lay them at his father’s feet. “Moreover he did not even keep his drawers but stripped himself stark naked before all the bystanders,” as recorded by Thomas of Celano, Francis’ first biographer, in Vita Beati Francisci.

Imagine standing in the midst of a crowd of curious onlookers watching a father berate and denounce his son, threatening him with an ultimatum that both father and son might regret for the rest of their lives. No one could have anticipated what happened next. Francis began to remove his clothes and lay them at his father’s feet. “Moreover he did not even keep his drawers but stripped himself stark naked before all the bystanders,” as recorded by Thomas of Celano, Francis’ first biographer, in Vita Beati Francisci.

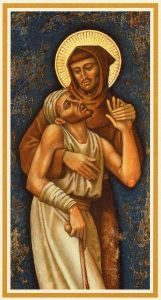

What does a father say to his adult naked son? What does a naked son say to his father? Who could write the perfect dialogue for the characters in that scene? Neither father nor son could have predicted a more startling set of circumstances that had brought them to that moment, and if each had paused to think about what was happening, they might have chosen another way of solving their differences; less public at least. Both men were impulsive: Pietro driven to exasperation in hopes of bringing a son to his senses, and Francis in his spontaneous and sometimes rash behavior in the desire to live for God. The bishop opened his robes and wrapped a naked Francis inside, a gesture that signaled the ending of one life and the beginning of another; an exchange of worldly attire for sacred garments. And in case there was any confusion as to the point of this dramatic dumb-show, Francis confirmed his action with these words, “Pietro Bernardone is no longer my father. From now on I can say with complete freedom, ‘Our Father who art in heaven.’”

What seared memories were created that day by such a raw performance on such a stage before a hometown crowd? As parents we want the best for our children, but sometimes our best intentions get in the way of a child’s natural interests and maturity. Certainly there are times when a parent must intervene, but it is an act of wisdom to know when to impose and when to restrain our will. If Pietro had not indulged and even encouraged Francis’ youthful follies or insisted Francis conform to his demand to follow in the family business, instead paid closer attention to his son’s growing spiritual inclinations, then such a public shaming might have been avoided.

For Francis, disrobing in the city center was his moment of transformation. How we come by our transformation is never really the point. Few of us will take the drastic measure of disrobing in public as a physical metaphor of transformation. The point is to be transformed regardless of time, place, or circumstance and it could be costly. Francis abandoned every worldly security and entered into a new life as a follower of Christ, incorporating into his soul the heart and mind of Christ, and allowing the love of Christ to flow through him onto others. When we embark on a spiritual odyssey that path will have its unique set of circumstances, encounters with others, and be shaped by our personality. But if the journey does not include a transformation of the soul that concentrates it on the needs of others by showing love and compassion to a culture obsessed with greed and power and self-absorption, then perhaps it is not transformation you seek. All we have left to us are our self-focused diversions, distractions, and entertainment. These things will soon bore the soul until it becomes numb to all human-made stimuli. That is a hollow life. Abundant life comes when our life is transformed by God’s love and then turns around and communicates that love to the world.