I was born into a world of whiteness: neighborhood, private school, and church; shuttled through that triplicate of colorless environs without wondering or questioning what other members of the human race might exist beyond those confines. At that time in my childhood my only exposure to other ethnic groups was when missionaries came to our church and gave slide-show presentations of their adventures in “seeking and saving the lost” in exotic places like Africa and Asia. It was the only time I ever heard my mother complain of our required attendance at church. “Lord, spare me from seeing another picture of a missionary posing with the indigenous people he’s baptized.” Such impiety from a worship leader’s wife.

When I was nine years old we moved to Bloomington, Indiana for Dad to begin his doctoral pursuit in music at Indiana University. We lived there two years, and my world was turned upside down. It started with our new residence: a second-floor, two-bedroom in an old army barrack converted into a multi-unit dwelling for less affluent families who were attached to the University. The apartment manager told my parents that if the building ever caught fire to grab the kids and run because the unit would be consumed in flames in fourteen minutes. They didn’t question the manager’s knowledge of the exact account of time from ignition to consumption of our new abode, but for weeks after we moved in, Mother was constantly sniffing the air inside the apartment for the least hint of smoke. I now lived in a more colorful neighborhood among people from all over the country, yea verily, from all over the world who had come to pursue their academic studies.

The cultural upheaval continued with my formal education. I now attended public school, Fairview Elementary, and with that came exposure to multi-national persons. I formed three close friendships that first year with a boy from Israel, one from Sweden, and a fellow American; a new type of American for me, an African-American, Raymond Brown. I felt an instant bond with Raymond probably because of the constant smile on his face that easily broke into laughter at the slightest provocation. Raymond looked at the world and found it humorous.

Raymond had the natural ability to run like an Olympian sprinter. Teachers would organize races during P.E., and even in competitions with upper classmates, Raymond would leave all the other boys in the dust. Sometimes Raymond allowed the other competitors a half-second head start just to make it interesting…for him. I distinctly remember his laughter as he blew by me with such ease as if he had his own personal tailwind. I wanted to be fast like Raymond, but alas, that genetic makeup was not issued to me at birth.

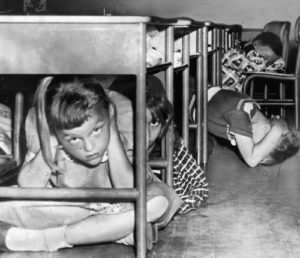

One day after coming inside from recess, Raymond and I still had some energy to burn and we began to scuffle. Isn’t that what boys do…scuffle? The teacher had yet to enter the classroom so we had no fear of her reprimand. Our bodies got entangled, and we fell upon one of the desks on the back row. It was one of those wooden and metal desks that were supposed to protect you from the bomb. We practiced regularly scrambling under our desks in preparation for that moment when the big, bad Russians dropped a missile on our heads. Such a drill for such an outrageous contingency was one of many things Raymond found humorous. He had no intention of crawling under his desk if a bomb were to drop. He believed with his speed, he could out run any blast wave of a nuclear bomb. Who was I to argue? Our desks were more dangerous as an inanimate object with its hard, sharp edges than as protection against the threat of nuclear annihilation.

Raymond and I crashed onto the floor beside an upended desk. We had only seconds to right the desk, get in our seats, and feign an expression of innocence before our teacher entered the room. But after we re-positioned the desk and put the spilled contents back inside, we noticed that we were bleeding as a result of our playful scuffle: I from a cut finger and Raymond from a nicely skinned shin. I credit the idea to Raymond, but I was quick to agree. “Let’s be blood brothers.” So I squeezed the minor cut on my fingertip to encourage ample blood flow and then smeared it all over Raymond’s leg. Order was restored from chaos and we became instant brothers for life. And if science and biology were in my favor, Raymond’s blood cells flowing into my veins would give me Mercury’s winged feet. It was a perfect world.

Even in the winter months we had recess outside. The playground at Fairview Elementary had upper and lower levels separated by a high, rock retaining wall. On the upper level were the traditional swing sets, merry-go-rounds, and jungle-gyms. The lower level was an open area for organized games like baseball and capture-the-flag, and in winter when the ground was covered in snow, supervised snowball fights. Snowball fights were only allowed on the lower level, and it was against the rules to throw snowballs from the upper level down onto those playing in the lower level. Among our contemporaries, Raymond and I had our social, cultural, and anthropological critics—he being black and me with my funny, southern accent—so when we happened to spy some of our school nemeses playing in the snow on the lower level, we seized the moment and rained down some snowball retribution on the bullies from our higher-ground advantage.

The victims of our attack did not need to report the incident. Our classroom teacher was an eyewitness, and when she blew an angry blast from her whistle, all the children on the playground froze as if the White Witch from Narnia had materialized. There were any number of ways to handle the situation, but our teacher chose the firing squad as her punishment of choice. She marched us down to the lower level and ordered us to stand against the retaining wall. Then she hastily scratched a jagged line in the snow with her rubber-booted foot and told all those who had suffered under our assault to assemble behind it. In her rush to judgment, the teacher did not bother to specify the real targets of our revenge, and consequently, more kids confessed to being victims than was the actual number. She told the gathering crowd to make their best snowball, and upon her whistle, to fire. What kid in their right mind would pass up the opportunity for a free shot at a stationary target? At least we weren’t blindfolded or tied to a stake, but surely our teacher must have escaped Nazi Germany where she had taught the children of the Gestapo.

While the kids dug their hands into the snow and began shaping the white powder into a small cannonball, I looked at Raymond. The smile on his face reflected a certain gallows humor at our current predicament. I was praying for a Russian bomb to fall from the sky right about then, but Raymond had a different idea.

“We don’t have to take this,” he said. If he was planning on running I knew with his swiftness, he could outrun the velocity of any snowball. If that was the case, then my only hope was for Raymond’s blood cells flowing through my veins to propel me out of our dilemma alongside him. But this was not his course of action. “We’re fighting back,” he said, the smile still in place across his lips.

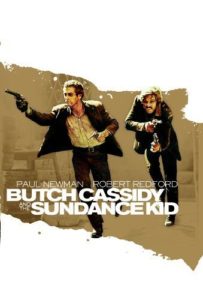

Raymond was not asking for my opinion, but I didn’t have to be told twice. We were blood brothers, and we would go down fighting together. The second before the teacher blew her whistle, Raymond and I scooped up some snow compressing the powder in our hands on the run. Raymond’s genes must have kicked in because we rushed our executioners, side-by-side, like Paul Newman and Robert Redford at the end of “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” and the playground erupted into a snowball free-for-all.

When Raymond and I were mixing our blood from our earlier wounds, I was not thinking about Civil Rights, or unity of the races, or one small step for mankind. I just wanted to be fast like Raymond and this transfusion might do the trick. It was never to be. There were no land speed records in my future. I needed more than Raymond’s blood to improve my skill as a runner. But Raymond Brown gave me more than an infusion of his precious blood. That day on the playground he showed me his true character. He stood for something, but more than that, he did not stand still. In the face of superior odds, he dashed forward braving the onslaught. Until that day on the playground, all my enemies were imaginary, played in childish games of battle. That day my foes were real and I was afraid. But Raymond inspired my heart with courage, and I followed him. Yes, I lived to tell the tale, and yes, I was proud to follow him.