In February of 1983 I went on a road trip with six other men to attend a spiritual renewal conference in North Carolina. I was the only actor in the group. Five were musicians and the sixth a pastor. A thousand or so people would attend this three-day event. The musicians would give concerts and lead corporate worship, the pastor would be one of many speakers and seminar leaders, and then there was me, the actor. I don’t remember how I got this gig or how I landed on the Saturday night docket. That specific night was not slated as a Christian vaudeville show where a number of acts would have five minutes of stage time. I was the only act. I had no name recognition or a long list of artistic achievements that qualified me for this prime-time opportunity. But I was in the van with these six men headed to the conference and was charged with the task of performing my one-man show “The Voice of the Lion” on that Saturday evening.

Four years prior to that February weekend, shortly after Kay and I were married and soon after discovering “we” were pregnant with our first daughter, Kristin, instead of doing something responsible, i.e., find stable employment, I decided to write “The Voice of the Lion,” a play about the apostle Paul. Then, after Kristin was born, I made the decision to throw what possessions we could cram into our Volvo, including our four-month-old daughter and her baby bed, and move us to Spokane, Washington to finish writing the play with a dear friend who had been the artistic director of two national theatre companies and had moved to the state the year before. He had connections with theatre and film companies on the west coast, and we had high aspirations of raising large amounts of capital to launch a big production of the play that would incorporate multiple stages, lazer lighting, and holograms. Yes, holograms; good enough for George Lucas, we argued, so why not for the leading apostle of the first century church? And how else were we going to pull off the Damascus road experience on cue night-after-night without a hologram?

Kay was a reluctant, yet devoted partner in this scheme. It was not an adventure she would have envisioned or embraced, but she was then and ever has been, supportive in my artistic leaps of faith or foolishness even when they would cause her internal turmoil.

After a year out west hard-charging to get a production funded and mounted, to no avail, Kay informed me that “we” were pregnant again with our second daughter, Lauren, so with my tail between my legs, we threw our stuff back into the Volvo and headed home to Nashville. I had a second opportunity to do the responsible thing: get that “real” job, but chose instead to transform the “Lion” dream from a quarter-million dollar spectacle into a one-man show with a set that consisted of two benches. The Saturday night of that spiritual renewal conference of 1983 in a mountain retreat center in North Carolina would be the world premiere of that modest, one-man/two-bench show, a far cry from the original price tag and no hologram in sight. The Damascus road experience would have to play out in the audience’s imagination. The whole prospect frightened and humbled me.

But it was an experience the night before that brought me to a deeper place of humility. The seven of us gathered in one of our rooms after the scheduled events that Friday for some late night conversations. We sat in a ragged circle around the room. I have the general remembrances recorded in my journal, but I did not note how it began. I just know who began it…the pastor in our group. He rose unobtrusively from where he sat, found a container in the room, and filled it with water. He took a used towel off the rack and slung it over his shoulder. No conversations were interrupted or halted by this action. Few of us were really paying much attention.

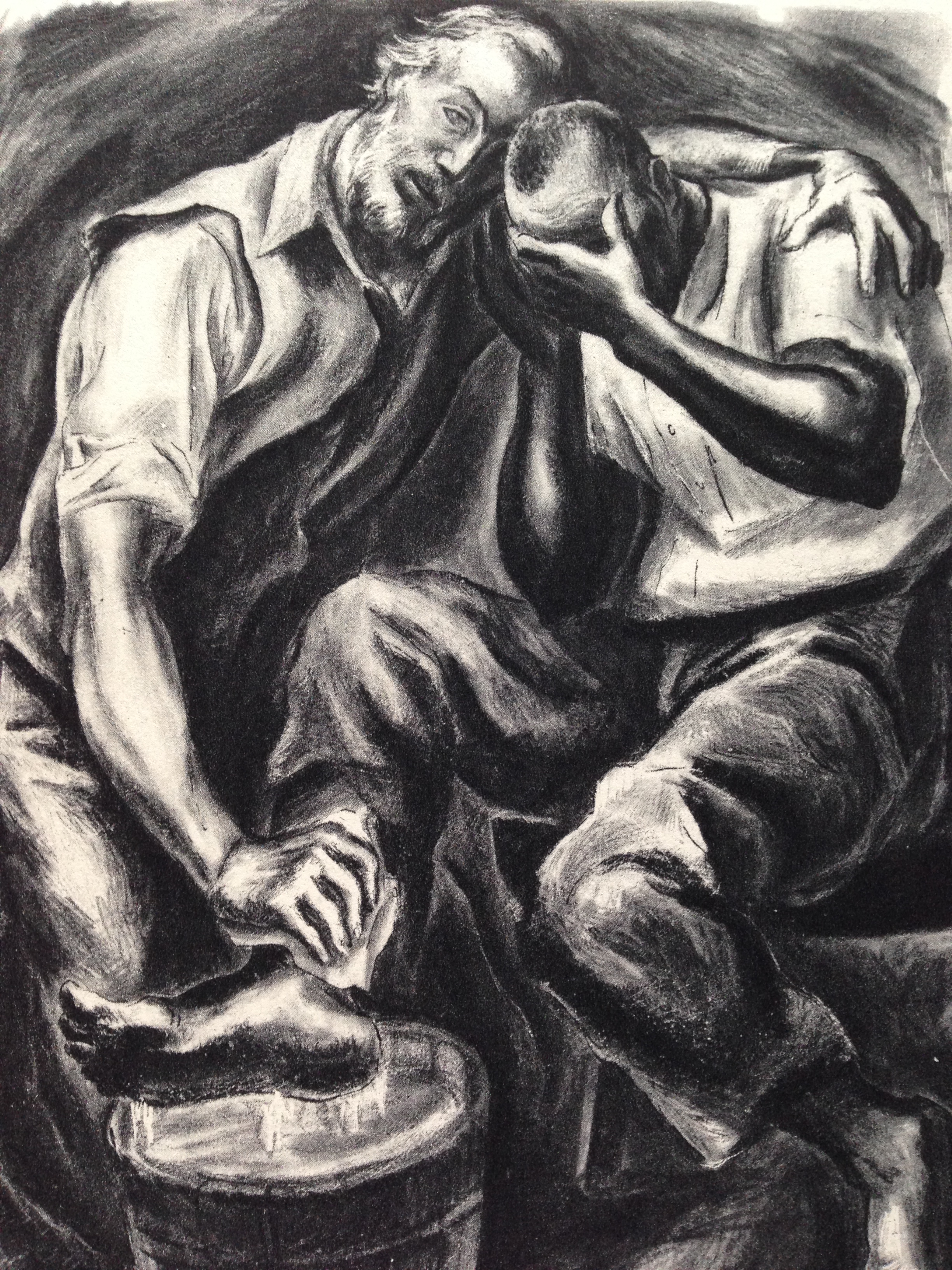

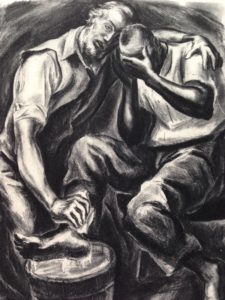

I’m not sure when I became conscious of what he was doing; probably not until he began to unlace my shoes. The talk continued but was more subdued. The pastor did not ask for silence or indeed for anything to stop on his account. In fact, he continued to engage in general conversation—laughing at how someone had forgotten the lyric in the middle of a song or the beauty of our hike in the snow that day—while going around the room, one-by-one removing six pairs of footwear, and washing our feet. This was attention-getting not for the unusual nature of the act, but for the fact that he diverted our attention away from it by talking about anything other than what he was engaged in doing. He did not pray or offer a homily; just treated the act almost as if it were any mundane activity, and with this approach, he deflected any awkwardness we might have felt in the moment.

What was a common practice in ancient times, done more out necessity than for religious ritual, and performed by the servant/slave class on their superiors, Jesus Christ transformed into a holy act that equalized all human beings: no one was to be considered greater than another, and when you serve others in any capacity, that humble act has the transcendent power to make you happy, joyful, blessed.

After four years of collected failures and disappointments for the efforts made in behalf of the “Lion” dream, this foot washing moment freed me to be joyful in the act of my performance, yet at the same time, it brought me low. Twenty-four hours later I slipped onto the stage in the black and hit my mark spiked between two benches my father loaned me from his theatre department. And ninety minutes later following a standing ovation, curtains closed and house lights up, I took a few faltering steps upstage out of view behind some sound equipment and fell prostrate on the floor and began to sob. After a few moments, I felt a someone fall upon my back and begin to weep with me, and then a second body fell on top of the first, he too joining the sobbing chorus. It was a dear musician friend and the pastor. The weight of these two men (we remain life-long friends), all three of us weeping, was a burden I gladly bore.

Whatever humility I may have at any given moment in my life is usually forced upon me. It is not a virtue that resides naturally in my soul. That foot washing moment in February of 1983 was profound; so much so that twenty-five years later when writing the screenplay “The Second Chance” with Steve Taylor and Ben Pearson, a foot washing scene was written into the story. It is a seminal moment in the movie that alters the lives of the two main characters who are experiencing racial conflict. The first major religious conflict within the early Christian church was based on racism. Sad to say little has changed in the last 2,000 years.

In these recent days our country (and the world) has been devastated by violent events that have left us all confused, sorrowful, angry, and vulnerable. There has been a great deal of discussion concerning the causes for this racial and religious violence. Much of the discourse is thoughtful, reflective, and sound with numerous solutions offered for fundamental changes. In spite of the tragedies and traumas that devastate and divide us, there is much in our human fabric that unites us: we all struggle in life; we all have grievances; we all feel threatened from time to time; we all oppose injustice; we all want true equality.

If there is a truth reflected in the phrase, “Made in the image of God,” it must be that there is a core goodness within us because everything he created he said was “Good.” And for this goodness to thrive, we must live in community seeking the good in and for others. This goodness is not unique to a specific race or culture, nor is it relegated to an idyllic historical past. Goodness arises from an individual’s soul that gets reflected in our common humanity. We do not need to succumb to fatalism. We can actively shape our future. We are a people who give of ourselves. We are a nation of healers and comforters. We are a country that transforms optimism into service for others. It is hard work maintaining a core, God-given goodness, but the task is made easier when the effort begins with humility. If we have to begin somewhere why not with a container of water, a towel, and a bent knee? From that posture perhaps we can better examine the condition of our heart before we judge the heart of another.