In the days of my youth I had numerous unpleasant experiences of being part of a large group only to have it split like an amoeba in order to engage in a competitive activity. I so desperately wanted to fit in; and please dear God, don’t let me be picked last as the teams are chosen because it would only confirm that my talent (usually an athletic competition), is considered well below average by my peers. Consumed by anxiety in those days, I dreaded the athletic events where high achievers in the sport—dodge ball, basketball, flag football, etc.—were designated leaders of a team, and the Darwinian process of selection was used to determine the competitive sides. As names were called out, the chosen would stand behind their leader and whisper advice in his ear as to who might be his next best choice. I was never the last man standing.

I usually ranked between mid-to-penultimate choice, and I don’t ever remember hearing groans from my fellow teammates when my name was called. Still the whole process was an exercise in humiliation. One year in high school I did make the basketball team but kept the bench well heated with three other boys. The four of us were allowed to play only if the score favored or disfavored us by twenty points and with less than two minutes on the game clock. With so little time left to play, what harm could we do?

Once I became an actor I found myself, on occasion, with other professional artists engaged in art-related workshops and seminars. We would often be asked by the seminar leaders to form a small group to do an exercise. While the expectation to perform or compete was nil, I still felt the anxiety of being chosen. I sought out those folks of similar disposition and felt the gravitational pull of like-kind. The profession I chose is competitive and the selection process to find the right person for the job is daunting. As Martin Scorsese says “more than 90% of directing a good picture is the right casting.” Early in my career, I got an object lesson in knowing my limitations and the objectivity of being chosen to fit a role. What I experienced cannot be taught in any scholastic environment or workshop or professional seminar or program.

Now when it comes to creative talent my father and sister had/have it in multiples: Dad could act, sing, teach, direct, play an instrument…a quintic threat; then my sister, Nan Gurley, is a quadruple threat: act, sing, dance, and play an instrument (now she is an established painter, so after this I’m going to crawl into a hole and die). By the harmonic confluence of genetic design, I consider myself fortunate to have one of those talents.

In 1973, I was home from Pepperdine University for Christmas break. Nan was also home from Abilene University, and we learned of auditions for singers, dancers, and actors for the Opryland theme park that would open in late spring the next year for its second season. Nan and Dad helped me prepare my sixteen bars of “I Got Plenty of Nothin’” (a number I have used for many an audition but it has only landed me one role…the character of John Dickinson in Nashville Repertory Theatre’s production of “1776,” my first and last musical with that company). The Opryland audition committee had not requested a three-minute classical/contemporary monologue, something I could have pulled out of my back pocket. No, they wanted song and dance. So I warbled my sixteen bars followed by the dreaded dancing audition. My religious upbringing had no tolerance for dancing in its list of “absolutely not,” so I was at a distinct disadvantage. The choreographer called a group of auditionees to the stage and demonstrated a series of combinations we were to perform. After a hasty review of the dance moves, the piano player started playing and we were off to the races. I positioned myself in the back of the pack and tried not to fall on my face and bloody my nose. A half-dozen or more of the artistic staff, including Paul Crabtree, the artistic director for Opryland, sat behind long tables watching our moves, nodding their heads, whispering to each other, and in my case, trying not to laugh. Once we were dismissed, I knew theme parks were not in my professional future.

After Christmas I returned to Pepperdine for my next semester. I thought I might stay in L.A. over the summer and pursue the beginnings of a film career. Then late one afternoon I got a phone call. It was one of the casting people from Opryland asking if I could come for a callback. Trying to conceal my surprise that I was being considered, I politely said “no” for two reasons: 1) I’m in school in L.A. and have no money to fly home to humiliate myself a second time; and 2) there has been no improvement in my song and dance skills since Christmas. I thanked him for the call and we parted as friends.

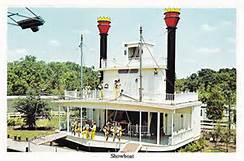

To my greater surprise a few weeks later, I got a second call from the Opryland casting person saying I had been cast in a show called “The Showboat Show” written and directed by Paul Crabtree. They had either reached the bottom of the barrel or my playing hard to get had worked in my favor. When Nan called and said that she had also been cast in the show, I thought, the film career could wait. I would work at Opryland for the summer, make enough money to pay the balance of tuition after scholarships, and go back to Pepperdine in the fall for my last semester.

Leap ahead to the beginning of rehearsals for “Showboat.” If my memory is correct, there were seventeen cast members. The show Paul Crabtree wrote incorporated a mixture of old standards like “Old Man River,” with contemporary numbers like “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown” and an instrumental version of “Shaft” for a big dance number. The set was the façade of the bow of a steamboat and the outdoor setting overlooked the Cumberland River. Crabtree had also written narration tying the songs and story together.

During rehearsals all the cast members auditioned for musical solos and featured dance numbers. I croaked through “Old Man River” and “Leroy Brown,” before being put through our dancing paces. The choreographer gave the cast a more complicated routine than what we were given at the first audition. I was that guy in the opening credits of the Bob Fosse film, “All That Jazz,” where the stage is packed with dancers doing a routine and that one guy who is a beat behind and bumping into other dancers. My ultimate mortification came when the Opryland choreographer had each cast member dance across the rehearsal hall in a diagonal line like the floor routine of a gymnast while dancing a combination she had designed. Since I could not hide behind anyone, I tried to make it across as fast as possible without twisting an ankle or breaking a bone.

The cast gathered in the middle of the rehearsal hall while Crabtree, the choreographer, and the music director confabbed and decided which of us would dance or sing what numbers. The triumvirate began to point to specific cast members informing them that they had been chosen for this song or would be featured in that dance number and then instructed them to go to their respective corner of the room. In a matter of a few minutes, singers and dancers were peeling away and standing to the right or left of the triumvirate leaving me in the middle of the rehearsal hall by myself feeling like the Elephant Man.

The choreographer huddled with to her dancers and the musical director did the same with his singers all of whom were giggly with excitement at being chosen for their featured moment in the show, which left Paul Crabtree to ponder what to do with the odd-man-out. All the youthful memories came flooding back with accompanying anxieties, and I now knew what it felt like to be the last one standing. I had been found out. There was no hiding in the background during the dance routines or just mouthing the lyrics in the choral numbers. It was a miracle I had gotten this far. I reviewed my options in my mind: wait tables, every actor’s default career, work construction, or Opryland might hire me as a character to walk around the park in an over-sized costume of a guitar or banjo or upright bass…not that there is anything wrong with that.

Crabtree approached. I’m not sure the squint in his eyes was one of pity or perturbation, but he stopped before me and said, “And you, my son, shall talk.” And thus the role of “Captain Jerry” was born. I would speak all the narration he had written. Crabtree had handed me the gift of knowledge. He recognized my one talent and gave me the opportunity to exploit it. I will always be grateful, and I’ve been doing my best to exploit it ever since. So far no one seems to have found me out.