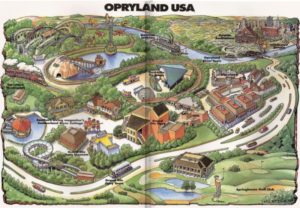

When I first began my career as an actor back in the 1970’s, there were not many professional opportunities in Nashville. The few theatre gigs I landed were not what could be called career-launching. So I headed west to advance my education. When I came home from Pepperdine University for Christmas break, Opryland, a theme park that produced variety shows with specific musical genres, was holding auditions for the upcoming season.

This was a great opportunity for singer/dancer/musician types, artistic forms that went beyond my limited abilities, but I thought I would audition, sing a couple of bars of something that would not humiliate me, and see what might happen. Wonder of wonders, I got a job in the “Showboat” show; a minstrel song and dance review that mixed turn-of-the-20th century tunes and dance styles with hit music of the 1970’s. There was one named role written into the show, Captain Jerry, who would narrate the story. The creative production team held internal auditions among the cast to see who of the singer/dancers would get what featured solos and dance numbers. After stumbling through my audition, Paul Crabtree, the writer/director of the show, looked at me with a droll expression and said, “And you shall talk.” Thus Captain Jerry was thrust upon me.

The park was open seven days a week, and two full casts were needed. Each cast worked six days a week and did 3-5 shows a day depending on the performance rotation. I did the role of Captain Jerry for two full seasons, and while I now pride myself in my professionalism, back then I was prone to mischief-making. Sometimes between shows I would dress up in a bright yellow, full-length slicker raincoat, sport a sombrero the size of an outer ring of Saturn, mount up on a thirty-six inch push-broom, and ride onto the stage of another show in progress, kiss a female cast member, and shout “El-Toro Pooh-Pooh strikes again,” then dash away. Another time I did an entire Captain Jerry speech in a German accent. It just so happened, one of the big-wigs from the Entertainment Department was in the audience and heard my sprechen deutsch monologue. A man born without a funny bone, he marched backstage and summarily suspended me for the next day, without pay. However, I was to come to the park and sit out my shift in the Entertainment office. I arrived the next day with a backpack full of plays to read.

The stage manager for our “Showboat” cast was from Brooklyn, and he had coveted the role of Captain Jerry from the first rehearsal. My infraction gave him his big break. That morning the big-wig who had suspended me sauntered through the reception area where I sat reading a play. He wore a patronizing grin on his face enjoying his little power trip of showing me who’s the boss. He was on his way to see the stage manager’s first show as Captain Jerry. An hour later he burst into the reception area. The big-wig opened his mouth to speak, but hesitated as if what he was about to say would cause him great physical pain. Finally he spoke. “Suit up,” he said, and stormed back to his office. Apparently, a thick Brooklynese brogue tripping off the tongue of Captain Jerry sounded worse than my bad German accent.

For this and many other sins, I was recast that following season as the Ring Master in a new “Circus Show.” It had no music theme, no singer/dancers, and no musicians; just me, a couple of clowns, the animal trainer, and her stable of performing animals featuring Mickey the Monkey. There was the obligatory dog and pony act, a couple of goats that did something forgettable, and a talking parrot whose clipped wings would barely get him from one side of the stage to the other for the reward of a cracker. In between the animal tricks, the clowns did their clown high jinks. In my Ring Master role, I would wax poetic about the circus and introduce each animal with its appropriate cute name. Mickey the Monkey is the only name I can remember. There was a stage manager who doubled as the sound engineer. The music was prerecorded calliope; the sort of music that will be played in hell on a continual loop.

The animal trainer was very protective of the creatures she had devoted her life training to be show animals. On the first day, she gave us a stern warning not to do anything she considered harmful to her precious ones. Truth was neither the clowns nor I wanted anything to do with them, cute and talented as they might be. It was the precious ones who fouled the backstage area filling our dressing room with a potent odor of livestock, and in the summer heat, made all the more pungent.

To say that Mickey was a chimp with an attitude was an understatement. I took lessons from him. In fact, I think we had a special bond. At that time in my life I was an off-again/on-again smoker. When the trainer wasn’t around, I would stand near Mickey’s cage and have an occasional cigarette. I would get this vibe from Mickey that he would love nothing more than to share a smoke with me. But of course, the female trainer would come down on me with the wrath of Greek Furies were she to catch me handing Mickey a lit cigarette.

Mickey was talented. His bag of tricks included playing catch, doing flips, jumping through hoops from perch to perch, and walking a tightrope suspended from a pole anchored at the lip of the stage strung over a pit and attached to a pole on the railing in the front row of the audience. Once he crossed the great divide, Mickey would shimmy up the pole, retrieve a preset treat on top of the pole, and then return back across the tightrope to the stage, turn to the audience and receive the expected enthusiastic applause. While he could do his job, he did so with all the energy of a washed-up alcoholic who was unemployable in any other capacity. Mickey was moody and all the trainer’s coaxing with treats and cajoling with kindness, was no guarantee that Mickey would do the trick when asked the first time. It was usually the third or fourth request before he would jump through that hoop or throw that beach ball. From time-to-time during a show Mickey would give me what I interpreted as an “I’m-so-over-this” look, but then fulfill his obligation to do his trick. Often he would get a post-show, “Bad Chimp” scolding from the trainer and a withholding of his favorite treats. On those occasions Mickey would sulk in his cage like the kid sent to bed without his supper. That’s when I really wanted to share a smoke with him.

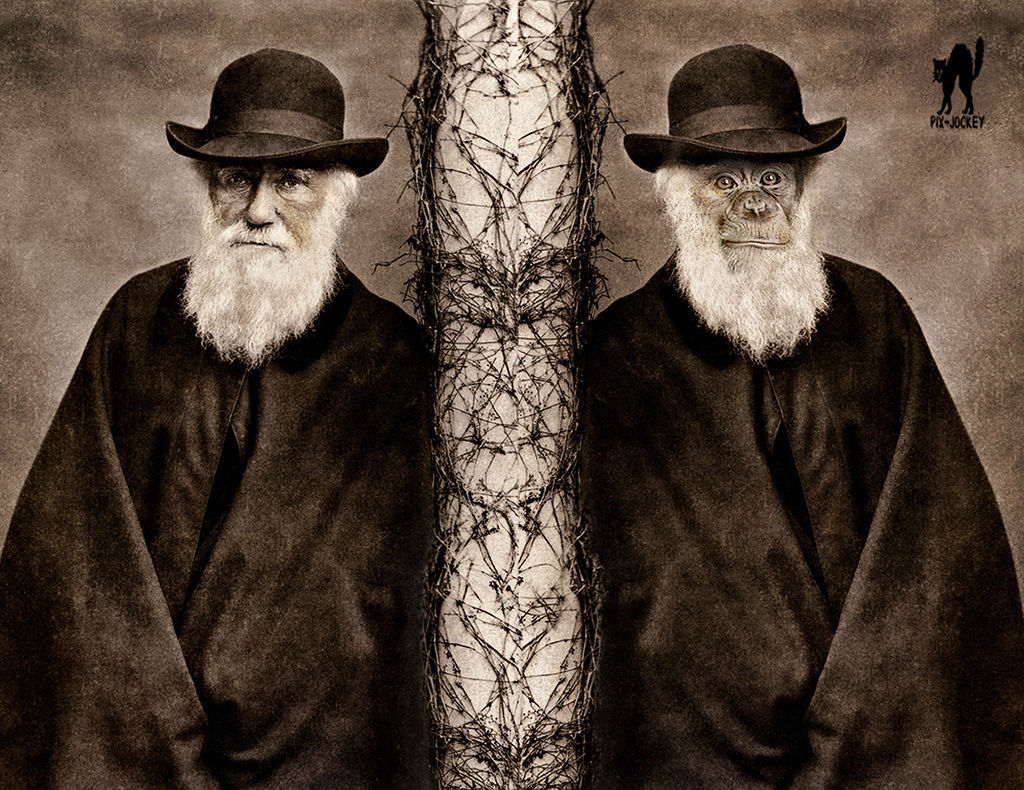

As Ring Master, I never needed to worry about irritating management. I was told by the big-wig at the beginning of rehearsals, “This ain’t Shakespeare,” (an understatement), and the “Circus Show” was a place he and the other big-wigs did not go. I could have done my monologues in any accent I wanted, rewritten the script into a lecture on the ascent of man, or switched roles with a clown. But my mischief-making-motivator was turned off for lack of inspiration. The reality felt more like a purgatorial punishment I must go through before emerging back into the light. But at least I had Mickey as my commiserating partner.

I don’t know how it happened; if Mickey woke up on the wrong side of his cage, or he and his trainer had an argument, or he ate something that didn’t settle, but on this certain morning for the first performance of the day, Mickey was just phoning in all his tricks. I knew he would be read the riot act at the end of this show. But his sour attitude changed when he got to his final act as if struck by sudden inspiration. He became more animated as he hopped onto his perch and started his monkey-walk across the tightrope, pretending to lose his balance halfway across to the delight of the crowd. When he got to the other side, he climbed up to his perch to get his treat and sat down to eat it.

Gloating with pride, he began a self-congratulatory applause, which induced the audience to respond in kind. Then the trainer commanded Mickey to return to the stage. Instead, he sat with his arms folded and a “you can’t make me,” expression. The trainer’s tone became more insistent and her repetitive command became a run-on sentence. What was fascinating was the reaction of the audience. They assumed this was all a part of the act. Only the clowns, the stage manager, and I knew that our trainer was staring into the face of monkey mutiny. She started yelling when Mickey climbed down the pole and began to lope along the railing of the front row of the audience. This was an outdoor theatre with tall trees all around. Mickey scampered up a tree on the audience-right seating bank with branches that hung out over the heads of the spectators. By now even the audience realized that this was not a part of the act and the monkey was now in charge. When Mickey reached the top branches, I half expected him to beat his chest and cry “FREEDOM!” but he did something better.

The trainer was apoplectic and the audience was beside themselves with joy at Mickey’s escape and the self-admiration of his antics. Then Mickey climbed onto a more limber branch and began to swing himself like the pendulum in an old clock, back and forth, first over the audience and then back the other direction. Each time he swung over the seating bank the audience would cheer. A few began to chant “Mickey. Mickey.” Not to be outdone, Mickey began to echo the chanting of his name with a staccato chortle of his own. In the middle of his final swing over the audience, he re-positioned his body, took dead aim with his rear end pointing it at the audience, and released a spray of excrement that looked like a plague of the apocalypse. The reaction by the audience was exactly like that in a war zone where the sound of the in-coming missile gives you a three-second warning to take cover.

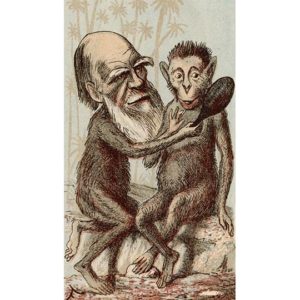

I had enough presence of mind to take the microphone and try to reassure the horrified audience. “If anyone has ever doubted the credibility of the theory of evolution, Mickey’s grand finale should lay that doubt to rest. That’s our show for today. Thank you, Mickey. Thank you, Mr. Darwin. And thank you, ladies and gentlemen.”

The next morning when the clowns and I arrived for work, the cages were empty, the backstage was cleaned out, and the trainer and her precious ones were nowhere to be found. Our stage manager greeted us like a town crier with the “Cancellation Notice.”

I never worked at Opryland again, but I went back a few times to see friends and my sister perform, and I always went by the theatre (transformed into a stage for rock n’ roll bands), and looked up into the trees and re-imagined Mickey’s moment of freedom when he swung from the branches, let out his ear-piercing screeches, and released…his inner King Kong. My only regret of the whole surreal experience of doing the “Circus Show” is that I never shared a cigarette with Mickey the Monkey.