Life will often surprise us with a dose of reality that rearranges our private universe in unexpected ways. The incident can be the equivalent of tasting the forbidden fruit. While the experience might expand the knowledge of ourselves and the place we inhabit in the world, it can also reveal something about our character we may have never known before leaving us feeling naked and in need of covering in a garment of fig leaves.

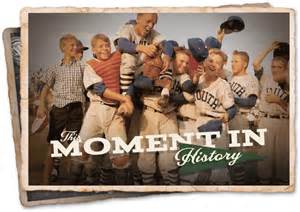

To belong and be accepted is a vital part of being human and central to our survival. I do not believe anyone who says they don’t care what others think of them. We are, in part, exactly what people think of us for better or worse. In this second chapter of “My Better Angel,” I write of the young protagonist’s hope to make the final cut of a Little League team. He arrives at the baseball field right after landing a job as a paperboy to hear the final verdict announced by the coach. The outcome makes an indelible mark on his soul. Though last month’s first chapter, “Staying Power,” and now this second one are told in first person, I again admonish the reader to remember it is only fiction.

Not a Team Player

In the heat of my first employment, I saw the world as fruitful. To have a job at my age with such freedom and responsibility would make my friends envious at my graduation from parental allowance to self-regulating earned income. I never could tell my friends I didn’t receive an allowance because my father’s income was unable to compete with the lawyers, doctors, stock brokers, and bank vice presidents who never blinked at the size of the checks they wrote to the private religious school we all attended. Allowance for my friends inspired more one-upmanship than any thought of gratitude, but I saw allowance as familial welfare, a way to manipulate and enforce authority. And I could imagine the girls at school awed in the presence of a boy who has severed the parental purse strings. I was stepping outside the safe confines of what I had known, and a flicker of potential new worlds stirred the juice in my system.

I coasted onto the Little League field where other boys, their parents and the coaches gathered at the stands. I parked my bike behind the bleachers and swaggered to the front trying to squelch the unchristian pride I felt at just having stepped into a wider world. In restrained tones I spoke to my schoolmates as I took a seat among the group. Every summer the school we attended sponsored a Little League team. Baseball was a rite of passage for the chosen few and we all wanted to be chosen. I thought being a future Wildcat would be an added breadth to my destiny.

I coasted onto the Little League field where other boys, their parents and the coaches gathered at the stands. I parked my bike behind the bleachers and swaggered to the front trying to squelch the unchristian pride I felt at just having stepped into a wider world. In restrained tones I spoke to my schoolmates as I took a seat among the group. Every summer the school we attended sponsored a Little League team. Baseball was a rite of passage for the chosen few and we all wanted to be chosen. I thought being a future Wildcat would be an added breadth to my destiny.

For days leading up to tryouts, baseball dominated the minds of my contemporaries. During the two-day tryout period where the coaching staff tested our skills of batting, running, fielding, and team compatibility, groups of boys would cluster to evaluate and discuss the athletic skills of potential teammates and predict who would be on the list. I tried hard to prove I could be a competent addition to the team, but I was not eaten-up with the game like my friends, most of whom seemed more concerned with becoming a Wildcat just to please their parents than for the joy of playing the game. Still I got swept into their enthusiasm, and thought it would do me good to be a member of a competitive team. I had played well during tryouts, catching a high percentage of all that was hit to me and batting above average, so I felt positive about my chances. My parents might have joined me for the big revelation had I asked, but I decided to face the outcome alone.

The rising sun began to warm the morning as I took a seat in the bleachers. I watched the parents huddled close and silent around their sons and imagined their confidential prayers nurtured the hopes that their pride and joy would be among the favored when the head coach announced the roister. I didn’t bother to waste a prayer for God to grant me a competitive edge.

The head coach, a failure in the world of sports beyond junior college, Little League being the highest altitude his star would rise, sauntered out of the dugout, clipboard in hand, ready to issue the invitations into the Wildcat kingdom.

“Thanks for coming out,” the coach said, his larynx strained to project beyond the first rows of the bleachers. He removed his Wildcat cap and wiped his damp forehead, an effective pause to hush the crowd and bolster the nerves. “I wish all you boys could be a Wildcat, but the League limits us to fifteen players, and it’s my job to decide who makes the team based on a combination of skill and team spirit. When I read the names of those who made the team, come stand behind me. Brewer. Fintress. Smith. Hartley. Patton.”

He was not reading in alphabetical order. Ambrose could be anywhere on the list.

“Wright. Hester. Brown. Turner. Shelton.”

I pictured Jesus calling the twelve disciples from a group of prospects and imagined Jesus reading the chosen’s names off a papyrus tablet: “Peter, Andrew, James, and John,” etcetera, etcetera. When the coach called a boy’s name, mothers squealed followed by an embarrassing bodily squeeze and fathers shook the boy’s hand or roughed up his hair before their offspring took his place behind the master. I wondered if the families of the twelve disciples reacted in similar fashion when their son’s name was called. The Bible might have been more interesting had the writers included those tidbits of human drama.

“Collins. McIntyre. Am . . . I . . . I mean, Armstrong. Corley. Shoemaker,” he said, and finished with a wave of the clipboard above his head.

The last five descended from the stands, and the coach raised his arms in welcome like Jesus welcoming the saints: “Well done, good and faithful servants; enter thou into the joy of thy master.”

All five fingers of my left hand were spread. Before that, ten fingers had matched each name. Maybe I had miss counted, my name was almost called. I watched the other rejects and their parents amble out of the stands listening to the parents offer comfort by promising exciting summer alternatives to their dejected sons, but I knew something was wrong. I approached the elect buzzing around the feet of their chief, the only one willing to question the authority of the list, and waited for the coach to send his team to the field.

“All right, boys. Free milk shakes at Compton’s Drugstore after practice. Now five laps around the bases and put some hustle in to it,” the coach said.

This year’s Wildcats tossed their gloves into the air and broke ranks with a shout. The coach basked in the wholehearted response to his first order until I diverted his doting.

“Yeah.”

“You almost called my name.”

“Mistake.”

“I thought I tried real hard.”

“Really,” he said, his face a reaction of surprise and disdain.

I took his one-word replies and his adoring gaze at the howling Wildcats running the bases, to mean an indifference to the castoff beside him.

“I thought . . .”

“Ambrose, you’re not a team player.”

“What does that mean?” I asked, stung and confused by the phrase.

“You don’t know, I can’t explain it to you,” he said tearing his eyes from his precious Wildcats and directing his frown at me.

I thought something must be wrong with me. Not being a team player must be a communicable disease and, were I to be in regular contact with the Wildcats, the infection could spread. I began to shrivel inside, the disease diagnosed and sentence pronounced: “Cast ye the unprofitable servant into outer darkness: where there shall be weeping and gnashing of teeth.”

“Got to get to practice, Ambrose,” he said before strutting toward the field. “All right you Wildcats, let’s hear a Wildcat scream.”

Fifteen Venetian voices strained hard enough to rupture a yet-to-drop testicle honored the command with a sound of fierceness. I stood there until my shock flushed into humiliation, then got my bike and pushed onto the road. I heard the coach call the Wildcats into home plate for prayer. With heads bowed, eyes closed and arms draped over panting shoulders forming a Wildcat community, they appeared to be worshipping their leader as he held his cap over his heart and rushed though this religious obligation. I couldn’t imagine what he might be praying. What I could imagine was how the rejects felt when informed that their names had not made it onto the Lamb’s clipboard of life. Had Jesus given the rejects the same line as the coach had given me but some sensitive monk had edited it out of the Bible? Perhaps the monk suffered from the same malady.

Fifteen Venetian voices strained hard enough to rupture a yet-to-drop testicle honored the command with a sound of fierceness. I stood there until my shock flushed into humiliation, then got my bike and pushed onto the road. I heard the coach call the Wildcats into home plate for prayer. With heads bowed, eyes closed and arms draped over panting shoulders forming a Wildcat community, they appeared to be worshipping their leader as he held his cap over his heart and rushed though this religious obligation. I couldn’t imagine what he might be praying. What I could imagine was how the rejects felt when informed that their names had not made it onto the Lamb’s clipboard of life. Had Jesus given the rejects the same line as the coach had given me but some sensitive monk had edited it out of the Bible? Perhaps the monk suffered from the same malady.

JESUS: Daniel, Ezra, Jehoshaphat, Caleb, Michael, you can’t go and save the lost. You’re not team players. (The Castoffs retreat down the Mount of Olives.)

My body trembled from the mortification, and I struggled to mount my bike. Once on the seat, I rode too far into the road forcing a car I did not see coming up behind me to slam on its breaks, then added to the insult by blowing the horn causing everyone on the field to look at me riding like a circus clown over eager for laughs. I sped away trying to get out from under the idea of a heaven that could enforce outcomes on people’s lives like an amusing game played by the inhabitants of heaven hard‑up for entertainment.

INHABITANTS OF HEAVEN: Let Us cut Michael from Little League and watch his course of action. Oh look, he was almost struck by a car. (Heavens rumble from Inhabitants’ laughter.)