The first time I questioned my sense of belonging came a few seconds before a near-death experience; nothing like your own personal NDE to make you sit up and take stock of your life, the world, and the universe at large.

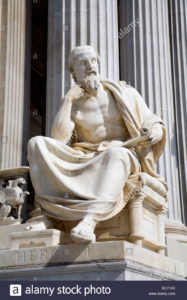

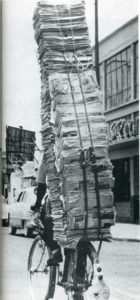

At the age of twelve I got my first job as a paperboy. For the next four years, morning and afternoon, I peddled just over seven miles through the neighborhoods near where I lived slinging The Tennessean and The Banner into the driveways of my subscribers. The tubular newspapers secured with a thick rubber band were stuffed into a large metal basket mounted on the front of my bicycle and two saddlebag-type baskets attached over the rear wheel. The paperboy motto was similar to the unofficial creed the U.S. Postal Service adopted from Herodotus’ description of the faithful couriers in ancient Persia of the 6th century: “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.” A subscriber expected to receive his daily paper as much as he expected his daily mail. I was depended upon, and the responsibility made me feel like a man of the world.

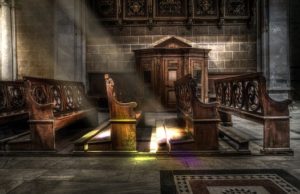

Six days a week I could handle the deliveries on my bicycle, but the size of the Sunday paper was monstrous—half news, half advertisements—and the subscribers for the Sunday paper nearly doubled as well. This required parental assistance. So I struck a bargain with my dad: he would drive me on my Sunday morning route, and then we would head to church and I would help him fold and distribute the “Order of Worship” programs in the hymnal racks on the backs of the pews. It was a mutual benefit, but with one glaring difference. I would often complain about having to keep my end, while Dad never complained. It was one of many disparities in our personalities.

Dad was given a paltry budget from the church to pay for the hundreds of programs used each Sunday, enough to purchase the paper to make the copies. He was meticulous in choosing the front cover: scenes of nature, paintings of Old Masters, sculpture, stained glass, of sacred spaces and illustrated scriptures; all images designed to frame the hearts and minds of the congregant for worship. The measly amount devoted to such innovative extravagance did not pay for the actual printing costs. After typing the original mock-up of the program, Dad would head down to the basement, pour in the chemicals for printing, and then hand-crank each copy on the mimeograph machine. I can still hear the rhythmic ka-chunk, ka-chunk, sound rising beneath the floorboards from the circular motion of the handle. One revolution spat out one program. Sometimes Mom would work the machine while Dad folded the programs, and on occasion, I was commandeered to do the cranking. The printing chemicals caused my eyes to water and gave me headaches. The fumes probably killed a few million brain cells each time I worked the machine. (I know. That it explains everything.)

Dad was devoted to elevating the worship experience above the dry formulas of the day. Probably an influence of the Episcopal chaplain he assisted while serving in the Army. Dad told me often he considered himself a “closet Episcopalian.” His effort to bring a high-church aesthetic to the act of worship began with a thoughtful preparation of the best hymn and scripture selections for each service, and he carried it through to mixing the fume-inhaling and the eye-burning chemical concoction, to the ka-chunking, to the folding and the placement of each program in the hymnal racks in an empty sanctuary early on a Sunday morning, and finally to his exquisite leadership in guiding the individual into a corporate involvement of worship. Dad was so ahead of his time.

My internal sense of displacement, which had been building in my young heart for some time, came to a head on one particular Sunday morning. I considered my parents “a little lower than the angels.” I had yet to discover their feet of clay; that discovery was a later revelation, and then in future years, came with more distressing implications once I became a parent. But in my early teens, after observing their collective goodness, I began to doubt that I was their child. They were high-quality human beings, and as a teenager, I was becoming undone by “the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to.” Based on their model of behavior, I sensed the miss-match in the gene pool.

“Was I left on your doorstep when I was a baby?” I blurted, and Dad almost choked on his coffee before turning onto the first road at the beginning of my route.

I rolled down the back windows, and Dad slowed the car so I could sling the papers in the driveways on each side of the street. He was amazed that I would think such a thing until I pointed out that I felt so different from him and Mom, so different that I could not possibly be their progeny. “Different how,” he asked, and I took the activity of slinging the papers out the back windows as we crept down the road to ponder his question. How could I point out the disconcerting truth that the souls of my parents bordered on the saintly, while mine was developing into more shaded, carnal areas? Why didn’t I share their world view? Why did I not have their immutable faith, their ease with a well-regulated life, their free submission to our religious persuasion? In my mind, all these factors pointed to a suspicious origin.

I was not forthcoming with an answer, so after he made a ninety-degree turn onto another road, he eased the car to a stop beside the driveway of a southern-colonial mansion, complete with Greek columns, set off the road. A thick fog had settled on this cold Sunday morning, and I could not see the two-story mansion for the fog. I felt vulnerable, my soul in need of a concealing fog, as I tossed the paper onto the driveway. Dad put the transmission in park and turned back to look at me buried up to my waist in wrapped Sunday newspapers.

“Son, you are blood of my blood and flesh of my flesh; every inch an Arnold. Any differences we might have are your own uniqueness, what makes you you, the way God made you.”

That was reassuring and frightening at the same time. He was claiming me, but I did not want to confess that I felt as though I was drifting from the shoreline of the goodness of my parents’ beliefs into an uncharted sea that could swallow me whole. I was not sure God was happy with my implanted “uniqueness.”

“How can that be?” was all I could squeak out.

“It’s a mystery, but I have foolproof evidence at home.”

Dad thought I was asking for physical proof of belonging. My quandary was of the soul, not wholly a distrust of my genesis, that I did not know how to articulate. The earnestness and ambiguity of his answer brought me no peace of mind, and Dad put the car in drive and we moved on.

We approached an intersection where there was a stop sign for traffic coming from our left, but it was not an all-way stop. We had the right away. Just before reaching the intersection, a black Sedan, which should have come to a stop from that direction, instead, streaked out of the fog like some dark missile fired across our bow, never slowing down until it bounced over the ditch, and into the yard on the opposite side of the road, where it crashed into a concrete front porch of the small house on the edge of the mansion property inhabited by the caretaker and his wife of the landlord who lived in the mansion concealed by the dense fog.

“Would you look at that?” Dad said in amazement. He pulled off the road and we scrambled out of our car. The driver was unharmed due more to his state of inebriation than a lack of modern safety devices we have in our vehicles today. The caretaker and his wife burst out of the house and began to laugh. They cited inclement weather and alcohol as the main culprits for the additional function of their front porch to act as a barrier against runaway vehicles. They don’t build front porches like they used to.

The couple called a wrecker and the police, and we got back into our car. We sat for a minute observing the scene.

“Son, had we not pulled over, he might have hit us broadside. Thank God.”

He thanked God, but I was the one who asked the question that got him to stop. I was trying to keep my balance on the slippery moral and ethical ground I walked upon, and now this NDE had brought turmoil to my soul. But at that moment I was just grateful to be alive. I didn’t care who got the credit. It was a mystery. By belonging to my father, I had survived my first near-death experience.

We finished delivering the newspapers, but the accident and my existential crisis put us behind schedule. We raced to church and inserted the “Orders of Worship” into the hymnal racks, then raced home. To get the Arnold clan dressed, fed, and out the door for church was always a challenge. But on this Sunday morning my parents paused in their hurried preparations to get the flock out the door. Mom retrieved an old metal box from the top shelf of their closet, opened the rusty lid, and pulled out my birth certificate. I held proof of belonging in my hands with the embossed seal of the State of Tennessee stamped on the document. I ran my fingers over the raised lettering of the seal for the tactile assurance of what my eyes beheld. Easing the distressed soul of their first-born was more important than getting to the church on time.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks has said, “Belonging redeems us from our solitude.” Certificates are what the state requires as proof of belonging, but what gives the individual a true sense of belonging is when you hear stories shared among family and friends that feature you and reveal the shades of your personality that uniquely demonstrate a universal belonging to our common humanity.

I am grateful to have belonged to Bud and Bernie. I am grateful to belong to my lovely wife, Kay, and our daughters and their husbands, and our grandchildren. Kay and I are grateful to belong to our siblings and their families, and to the extended families that share our bloodlines. We are grateful to belong to the myriad of dear friends, from the long-ago to the present-moment, from the professional to the everyday, with whom Kay and I share joint-custody. And, above all, by the grace and mercy of the good Lord, I am grateful to belong to the kingdom of heaven…such a big tent…such a rich life of belonging…no certificate required.

Cover Art: Bud and Bernie Arnold