I was raised in an era when our particular church persuasion believed that we were the only ones going to heaven, and only then if you behaved according to the rules and had done enough “good works” to get in, and if not, well too bad. My own heart knew that I would never be good enough or do enough to qualify. It took me awhile to ask the question that if our church affiliation was so unsure about its future hopes of heaven how then could they be so sure that anyone from another denomination had no chance of making it? But if you were from the “true” church and you did make it, then you were part of a very exclusive club.

There is an old joke about St. Peter leading a group of new arrivals on a tour of heaven. When they get to a certain neighborhood in the heavenly city, St. Peter asks the group to remain silent as they pass by, “Because these people think they are the only ones here and we don’t want them to know any different.”

This notion of theological exclusivity is nothing new. The Catholics developed it into an art form, from indulgences to the Inquisition, and the Protestants co-opted their distinctive takes on salvation as the Reformation movement dissolved into splintered factions. This belief of being right on all points is designed to make the ones who believe they are right to feel superior and create human structures where oppression of others is allowed to thrive.

The same oppressive result happens among people groups whose tribal instincts encourage one race to feel superior to another. Bad things happen when that instinct is allowed to run rampant. I remember my parents facing down family members and others in their church community who held to beliefs of superiority in religion and race. It was a brave thing for a son and daughter of the south to declare that such beliefs were racist and wrong. They taught their offspring by example.

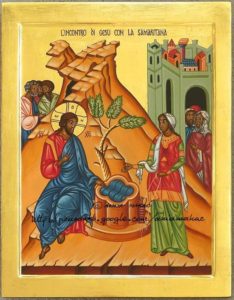

Jesus got into trouble when he embraced the outsiders of society; those who were marginalized because of race, economics, politics, gender, and even physical disabilities. He faced great opposition from the powerful elite and even from his closest circle of friends. The Samaritans were considered an inferior race in those days, and brothers James and John, dubbed the “sons of thunder,” were soundly rebuked when they offered “to call down fire from heaven” upon a Samaritan village for not showing the proper welcome to their leader. Such a story would be laughable were it not for the racial bias exposed in the passage and the arrogant, misuse of power the brothers’ thought they possessed. On another occasion, Jesus exposed their bigotry by treating the Samaritan woman he met at the village well with respect. When Jesus tells the famous story of the Good Samaritan, he is asking us to get over ourselves and embrace the other with love regardless of skin color or social status or religiously and politically incompatible beliefs.

Add sexism to the list of no-no’s Jesus kiboshed. He elevated the status of women in his respectful treatment of them. The fact that he entrusted the news of his resurrection to a woman was mind-boggling for that day and age. Mary Magdalene preached the first post-resurrection sermon in the history of the church—“He is risen. Go tell the others”—and she wasn’t believed by her male counterparts.

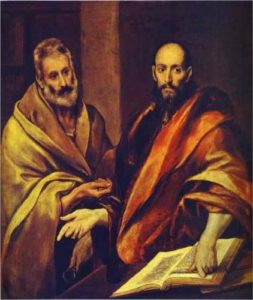

Then there was the apostle Paul who records in his letter to the Galatians about a time when he confronted Peter and those of his entourage who separated from the local members of the church in Antioch because of differences in race and theology: these were people of other nationalities who were uncircumcised. Paul went so far as to say that those “agitators” who insisted on the exclusive theology of circumcision if one was to be a “true” follower of Christ should just “go the whole way and castrate themselves.” Ouch! Paul could have done the polite thing and just called them hypocrites, but no. To castrate in Greek means the same in English. We can’t spin this into a spiritual metaphor.

So what do we do? Admit the truth. We are all guilty of racism either overtly or hidden in the heart. Whether we espouse a faith in God or hold to secular values, we are all guilty of feelings of superiority. When we look down on those who are different in any way, it is the action of a corrupt human heart. This corrupt condition starts in very subtle ways: telling lies, nursing grudges, refusing to forgive, revenging wrongs, selfish ambitions, societal and individual narcissism, sowing discord, being greedy, envious, or jealous. Every action we take reveals the condition of our hearts. How we treat others, how we act out our politics, how we conduct our business, the way we serve. Do we take a certain action for personal profit and advancement, or do make a thoughtful, compassionate decision for the benefit of others? Do I seek out only those who look, think, believe, and act the way I do? If you believe that God only likes the things you like and agrees with you one hundred percent of the time, then your god is you.

There is nothing new under the sun. Race and religion have always been hot-button issues. When hostile words fly through the air, when fingers of blame are pointed in every direction, good and innocent people suffer and die when this rancor is unchecked and turns to violence. One can place one’s hopes in some guru, teacher, politician, philosophy, capitalism, governmental systems, or your personal self-improvement/self-centric set of rules and try to follow any of these options to the best of your ability. The hard truth is, none of these options will have lasting effect, and when your hopes in others or in yourself fall short, you end up being your own judge, jury, and jailer imprisoned by a set of rules and expectations that failed.

I submit that we don’t need to find the best example to follow, and yes, I include Jesus in that list. He did not come into creation to just be a good example. No one can come close to his example, and the Sermon on the Mount alone proves he is impossible to follow. Jesus came as a substitute to stand in the gap for our corruptible human natures. He invites us all into the embrace of his love, and his willing sacrifice distinguishes him from any other great teacher, philosophy, or human system in the long history of the world. That is an eternal status not achieved by human effort. What a mercy. What an act of grace.

At the end of his life while living in exile on the island of Patmos, St John had a vision of heaven. He saw those celebrating around the throne of God “from every tribe and language and people and nation.” So if you are clinging to the false hope that your skin color or stanch beliefs make you superior to everyone else and that you expect your future mansion in heaven to be located in a neighborhood of like-minded, like-colored, and like-nationality as you, I suggest you go ahead and cancel your reservations. And should you find yourself in a different location after shuffling off this mortal coil, I leave you with this final thought from my niece, Erin Gurley: “Even there you will still find people who don’t look like you.”

Cover Art: Hieronymus Bosch; Ascent of the Blessed