One can find countless quotes on what it means to become a man from the humorous and profane to the solemn and profound. In my opinion, becoming a man is a process of making fewer and fewer stupid choices and putting more and more distance between each stupid choice. St. Paul said it best, “When I was a child, I talked like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child. When I became a man, I put childish ways behind me.” Transitioning from “childish” mode to “manhood” mode is not the simple flip of a switch. There is no magic age to mark manhood that come with frameable “Manhood Achievement” certificates. We get to drive a car at sixteen. We can vote and join the military at eighteen; smoke and drink at twenty-one; get an education and secure employment shortly after; eventually find a mate. None of those chronological milestones assure manhood, and the mix-messages we boys and men get from the DNA of our genealogy, culture, media, social milieu, and bad theology can end up piecing us together like an abstract painting: visually beautiful on the outside, bewildered and lost on the inside.

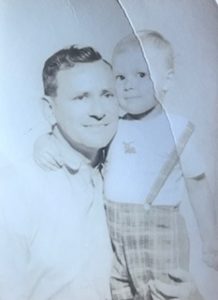

My long slog resembles Pilgrim in “Pilgrim’s Progress”; many foolish choices and wrong turns landing me in dark places with no sense of direction and no sightings of even a flicker of light. I needed rescue, and as I look back on that phase in my life, I didn’t even recognize my need for rescue. My father did. I believe rescuing came so natural to him that he was not even aware when he activated the impulse. He probably could not articulate how he came by such an ingrained virtue of his soul, and then would deny it if you attributed that positive feature to him.

We were estranged at the time my rescue began. In my underdeveloped, idiot brain, Dad’s coolness factor was low, which shows how little I was paying attention to him and to my own foundering in the “slough of despond.” As clueless as I was about my plight, I was equally clueless as to what was happening to me when the lifeline was cast.

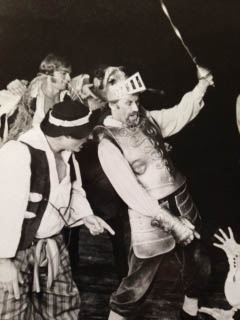

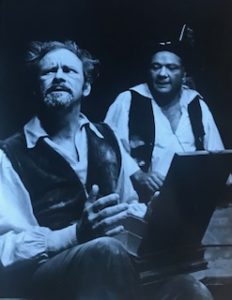

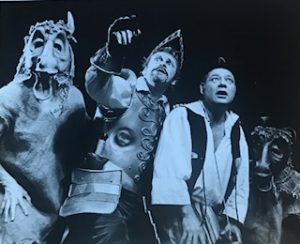

Dad was offered the role of Don Quixote in the musical “Man of La Mancha.” I was not aware of it, but my father had asked the director to give me a chance at a role, which the director agreed to as long as I went through the audition process. If I weren’t embarrassingly awful, then I would be given a shot. The bar they set was very low, but I did land the role of a muleteer, one that was a named character with a handful of lines, and not just a part of the mob. My character’s name was Paco, and I latched onto Paco as if my life depended upon it. It probably did. I showed up for every rehearsal. I was even an understudy for the role of the Barber. After my one and only understudy rehearsal, the actor originally cast in the role informed me not to get my hopes up. He had no intention of getting sick or dying in an accident during the run of the show. I took this as a compliment.

In the program section of “Who’s Who” in the cast, after my name and the name of my role, my bio read: “…making his Theatre Nashville as well as his acting debut…Hillsboro High School graduate…life guard this summer at Cascade Plunge.” My father’s bio was a little more fleshed out. I will only give you the first line of his paragraph. After his name and the name of his role, his bio read: “…where do we start?” I had a long way to go to catch up. When it came to the theatre, the “like father/like son” comparison would not become a reality for a long time.

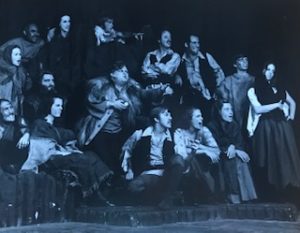

In rehearsals I watched how my father took direction, how he paid attention to what was going on around him, how he reacted to what other actors gave him, how he made manifest his physical, vocal, and interpretive choices for his character. He was gradually transforming, and though I did not understand what was going on, I remember that I was fascinated by this process. In a minor way, I was experiencing my own transformation with Paco, the Muleteer. I was becoming someone else, and I was with a company of other actors who were also experiencing a similar alteration. My father was spinning a magic, leading others into a dream, into an “impossible” dream of the possible.

It was not until we moved from rehearsal hall into the theatre where all the elements of production came into place for final dress that my eyes were opened to the possibility of transformation. There is nothing like the lights and sets and music and costumes and finally, the audience, that make an actor come to life and for art to happen right before your eyes. It was in this brief and mysterious set of circumstances I began to realize the power and importance of observation, of just paying attention. Night-after-night I saw my father transform from Henry Arnold to Miguel de Cervantes, and then into Don Quixote as he followed his beautiful quest jousting against evil, seeing the beauty in all things and in all people, even his enemies, until his eventual death.

When I was a child of four, I was traumatized when I saw my father plunge a knife into his chest as Billy Bigelow in the musical “Carousel” and die. This time I was not traumatized by my father’s death. I was in awe, in awe of my father’s skill as an artist, one who used his imagination to create a moment of transcendence. That was almost fifty years ago now, and that may have been my first experience of the power of art to transcend space and time and flesh and blood. It was my father who had led all of us, cast, crew, and audience, into that sublime moment of truth and beauty. If you are inclined, you may listen to Dad sing “The Impossible Dream” from that production back in 1970 by clicking the play button below. The dialogue exchange leading up to the solo is between Dad as Don Quixote and Pam Martin in the role of Aldonza. Special thanks to long-time friend, Alan Nelson, for providing this excerpt from the musical:

Dad’s subconscious “impossible dream” for this father/son/“Man of La Mancha” experience might have been that his son reestablish the filial bond, and if I wanted to give this story a happy ending, that is what I would write. It did not happen that way. Estrangement continued and any semblance of my manhood eluded me for years to come. Some of us are not easily rescued. For some, the lifeline for rescue must be a long rope; miles and years of coiled threads stretched to the limit. But whether I knew it or not, it was in that brief time with my father when I took hold of that lifeline cast to me, and it began the slow molting of my “childish ways.”

Up until his death, Dad and I did so many creative things together. I could begin that list with the same phrase as his bio for “Man of La Mancha,” “…where do we start…” One thing I do know, I will never grow tired of hearing people say to me after seeing me perform in a show, “You are so much like your Dad,” or “I saw Buddy up there tonight.” I hope I am like my dad in all respects. I hope they see “Buddy” in all my performances. I hope that transformation of father and son can be complete not just in the magic of theatre, but in life as well. I do know that in the case of my father, I agree with Solomon who wrote in Proverbs 17:6 that “…the glory of sons is their fathers.”

Cover Art: Dad as Don Quixote threatening a villain with me as Paco in the background.