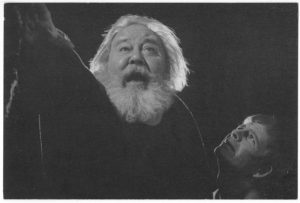

I love it when I have the opportunity to do a play because I get to go around using my Outside Voice without fear of Kay’s disapproval or a similar negative reaction from a host of others who might consider my volume level an infringement on their personal auditory space. During those weeks of rehearsals and performances I go about the house or tramp over the back field, my mind and body absorbed in my character, my voice modulating in tone and quality, as I search out just the right physical and vocal nuances that will lend truth to the moral fiber of my creation. Kay can only scowl at me when I’m “getting into character” and not scold.

Early into our marriage whenever Kay and I were having a disagreement she would stick her fingers into her ears and tell me to stop shouting. “That’s not shouting, my dear. That’s projecting. I make my living projecting.” Yes, her eyes rolled in exasperation then and still do today whenever I use that excuse for my increased volume.

On more than one occasion my Outside Voice has usurped my Inside Voice at improper times and gotten me into trouble. A notable moment took place in a church setting years ago when our girls were old enough to be sitting with us in the pew and still young enough to be indifferent to the service…much like their father. In the middle of the sermon when the preacher made an inane theological point that God’s love was contingent on us performing good works; the preacher’s line went something like, “Jesus is well and good, but you have to earn yourself a place in the kingdom,” I took immediate umbrage. I looked over at our little darlings seated between Kay and me, happily playing Tic-Tac-Toe on the church bulletin, and said, “Girls, what he just said is a lie.”

In my defense I did use my “stage whisper” voice. However, their heads shot up, the Tic-Tac-Toe halted in mid-contest, and they looked at me as if I had said something blasphemous. And so did the other congregants in a three-pew, 360 degree radius from where I sat. My stage whisper was the epicenter of a contrary theological viewpoint pulsating out in waves in every direction of the compass. Kay, while sinking into her pew, looked at me with a shocked expression that quickly turned into one of death, the “As soon as I get you home, you’re dead,” look. We all survived my poorly timed comment, and we never darkened that church door again.

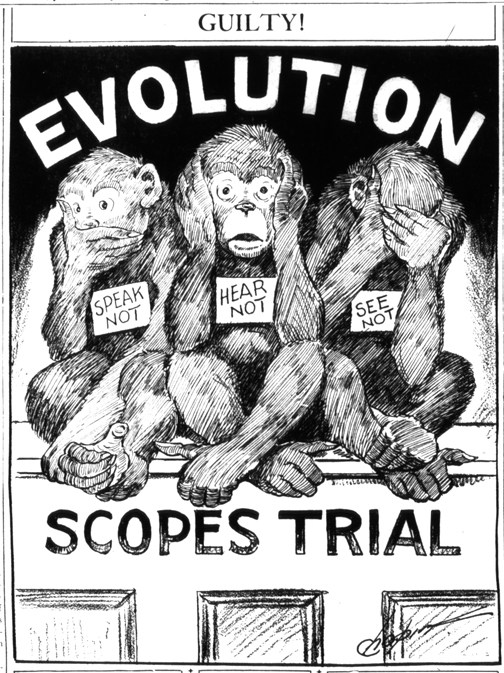

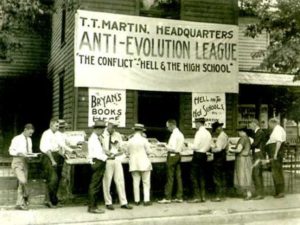

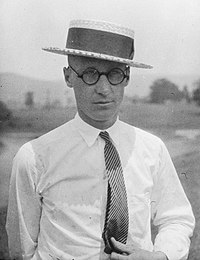

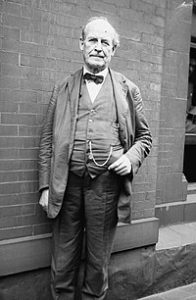

William Jennings Bryan, famous politician and orator of the early 20th century, had an Outside Voice. I am fortunate to be playing the character based on Bryan in the play “Inherit the Wind” produced by Nashville Repertory Theatre in March/April, 2018. (For more information visit Nashville Repertory Theatre website) The play centers around the Scopes Monkey Trial in 1925 challenging the legality of teaching the theory of evolution in the public school system. What began as a publicity stunt soon overwhelmed the city fathers when two hundred newspaper reporters from across the country, along with film crews and radio broadcasters, descended upon the small town of Dayton, Tennessee.

The Bible verses Charles Darwin; the Monkey verses Adam and Eve; Secularism verses Theology; a nationally known politician verses a nationally known lawyer: the stuff of great drama; something for everyone in this story. What might have been a local, carnival sideshow became the most widely covered debate between science and religion that had occurred in this country since Darwin let the monkey out of the bag.

Years ago Kay and I took a day-trip to Dayton. It was a roots trip for Kay, and she wanted me to meet the few remaining relatives still alive. Her father was from Dayton, and as fate would have it, he was a student of John Scopes in the short time Scopes taught biology at the local high school. When we arrived in Dayton the courthouse was closed, and after we walked around the property trying to look through the windows on ground level, we wandered over to the police station next door. After explaining the family connection and the purpose of our visit to the police sergeant, he handed us the key to the courthouse building and said, “Just be sure and lock it up when you leave.” This was definitely “back in the day” when family connections still counted for something and trust was a commodity of value.

The basement of the courthouse was a museum devoted to the Scopes Trial with dozens of black and white pictures and newspapers on display along with all kinds of memorabilia of the event including some camera and radio equipment used to film and broadcast the trial. From the basement, we climbed the stairs to the top floor where the trial took place and walked around the large room. For eight days William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow, two of the most luminous personalities of their day, argued passionately for the right of the individual to think about one’s personal faith and human origin and how science and theology together might enhance a person’s existence without fully explaining the mysteries of creation. It was eerie and profound for the two of us to be the only ones in the building, alone in the courtroom almost feeling the heat of the atmosphere not only in Fahrenheit degrees, but in the fiery rhetoric in that summer of 1925.

We locked the doors behind us and returned the key. We were told where we would be served an excellent home cooked meal at a local meat-and-three and thanked the police sergeant for his kindness. In the remaining daylight, we drove around the town square, and then through the campus of Bryan College named for the famous orator. After eating our supper at the recommended diner, we headed back home.

In front of the courthouse there are two statues, one of Bryan and one of Darrow, though the one of Darrow is a recent addition. Perhaps in our pluralistic America the good citizens of Dayton saw the importance of equal representation after such a momentous debate took place on their soil.

A couple of years ago we finished out the attic in our house. If Kay happens to be home when the creative urge comes upon me to work out the complexities of the character I have been cast to play, I will head upstairs. In the quiet space I will pace the floor, and in full Outside Voice, speak the words of my character mining the depths of his soul in search for those nuggets of truth that will make this creature fully human. Regarding the theme in the play “Inherit the Wind” where opposing beliefs are expressed and challenged, being fully human comes down to one thing: to think or not to think, that is the question. We all wish to be given the freedom and respect as a human being to think, and most especially, to think for ourselves.

Cover Art From: Evolution: A Journal of Nature